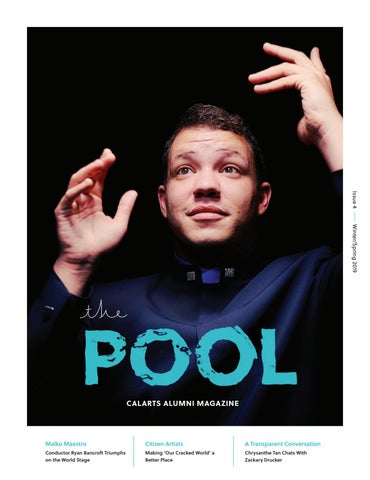

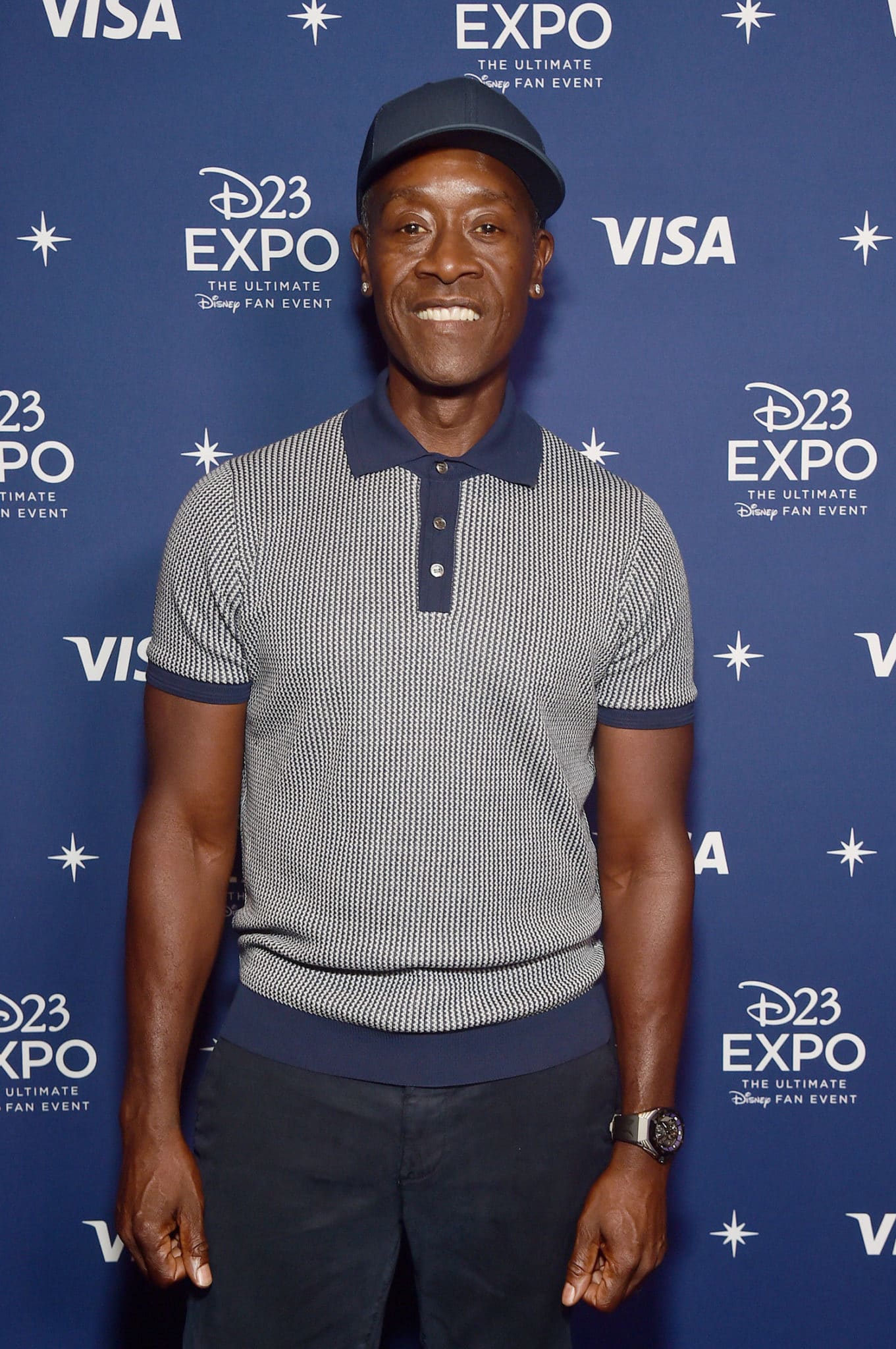

When Don Cheadle (Theater BFA 86) stepped from the stages of the Mod Theater and E400 to the sets of Hill Street Blues and The Fresh Prince of Bel-Air in the late 1980s, CalArts was a very different place—or was it? Recent graduate Jo Siri (Theater BFA 22) talked to Cheadle for The Pool about his journey as an artist, his influences, and the ongoing legacy of the CalArts Halloween party.

I felt the power of the stage and the power of performance and the ability to transform not only yourself, but to take the audience on a journey.

First of all, I’d love to hear about your journey. What brought you to theater?

What brought me to theater was just the expression of a latent performer who then became an actual performer. My family was very creative, with a lot of frustrated artists that had never done it for real. But everybody sang and everybody was funny, and we loved messing around and being playful with one another.

When I got to elementary school, I met a teacher named Barbara Althouse who was sort of our music teacher, but she would do all the play productions, choir, and all of the creative arts. We did a production of Charlotte’s Web, and I played Templeton the Rat.

It was the first time I had experienced theater in a formal setting. I felt the power of the stage and the power of performance and the ability to transform not only yourself, but to take the audience on a journey.

I was also very fortunate to have a great high school teacher, Kathy Davis. I just talked to her a couple days ago, actually. She introduced me to Uta Hagen and [Sanford] Meisner and great playwrights. She realized that I had an aptitude for it and said, “If this is something that you actually want to pursue, you should study it formally. And these are some of the schools where you can study it.” So she’s the one who introduced me to CalArts as well as Carnegie Mellon and NYU, places that had strong acting programs like Northwestern and Yale.

So it was through your high school teacher that you came to CalArts. Tell us more about that.

I had an audition at CalArts, and it was a really bad audition. I think I did a Molière. I kind of forgot the monologue halfway through and then thought, “OK, I’ll just improv.” I’m used to jazz [laughs]. The dean stopped me and she’s like, “I don’t know what that was. It’s a wrap, basically. We’re good.” And I said, “No, no, no, I have another piece. Let me do my other piece!” It was from The Shadow Box. And she was like, “OK, that was really good—because you were outta here after that Molière thing.” But somehow I got accepted, and I went to CalArts and spent four years there studying.

Do you have a favorite moment that you hold onto from your four years at CalArts? A special play, a workshop, a teacher?

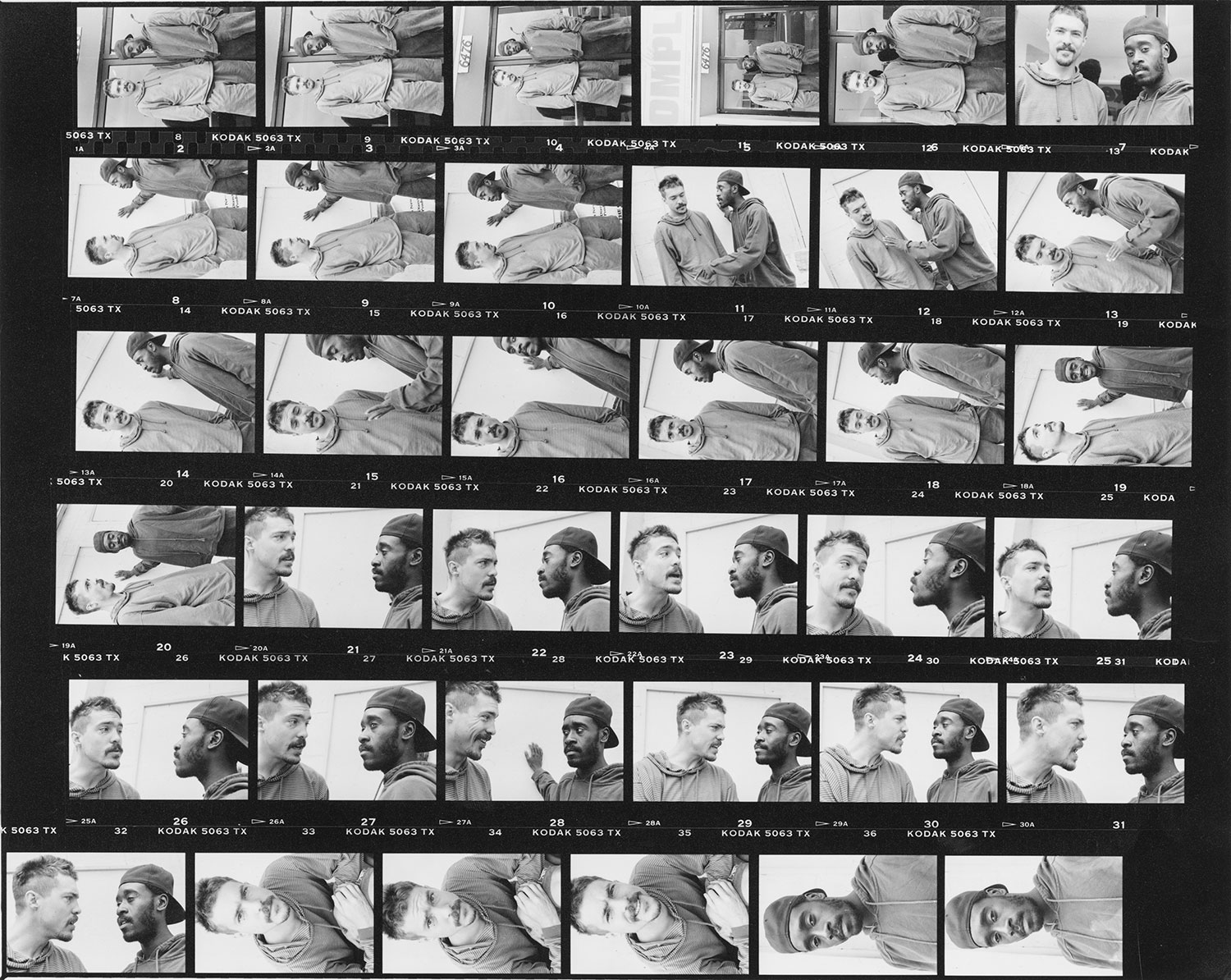

I had an amazing time at CalArts. I wouldn’t trade it for the world. The friends I made there are still lifelong friends. Jesse Borrego … his daughter is my goddaughter. She and my kids actually live together and are extremely close. Myself, Bruce Beatty, Geoff Thorne, Rhys Greene took the initiative and performed plays on our own in the Black Box Theater, no help from anybody. We just did ’em. We did Fugard plays, ‘Master Harold’ … and the Boys, and The Island, too. Everybody came. It was in one of those spaces above the Main Gallery … E400? Are they still up there?

Yeah, they are. During my freshman year, there were amazing student-led projects in E400. Students got together and made beautiful work. Now usually they’re in the Coffee House, and it’s still the same thing.

Really? That’s so wild. Yeah, those spaces were the space. Those were our main theater spaces. Those, and when you got to do something, obviously in The Mod, you’re like, “Whoa.” But most of our things were in those black-box spaces.

CalArts hasn’t really changed much.

I mean our Halloween party, my first year there, Los Lobos performed. And the Red Hot Chili Peppers.

No way. Are you serious?

Yeah, it was a great time. All of it. I loved Studio. I loved Tai Chi and took Tai Chi every year and learned the whole form. Sherry Tschernisch was one of my favorite teachers. Lou Florimonte, who was one of my favorite teachers.

Wow. They do capoeira now.

Where? That’s so wild.

It’s wild. They do it in the Main Gallery. I remember my freshman year, I was like, “Oh! OK, we’re serious. We’re getting down.” They would be straight up fighting in the Main Gallery.

Tai Chi really was something else that I took away from school that I love and still practice. When I got to school, I was 17. To have something like that, that was centering. That taught you how to just slow down and focus on one thing and tap into yourself. I thought it was a great addition to everything we were learning, and it was invaluable to me. I thought the program was very well constructed. It was hard, but it was really good.

I think my time at CalArts was all consuming. We were in the theater morning, noon, and night. When I attended CalArts, there wasn’t really an interdisciplinary program. On Wednesdays, our Critical Studies days, you had to take something in another metier, but actors weren’t doing movies for the most part, or doing voice-overs for animated shows. Some of us were doing that. But for the most part, we were doing Tai Chi, movement, speech, voice acting studios, script analysis, then crew; it was sunup to sundown.

Wednesday is still Critical Studies day for actors.

Which for us meant go to Ventura Beach and take mushrooms. But that’s off the record, right?

I mean, that’s still pretty similar.

Yeah. OK. Then it’s on the record.

Don Cheadle’s Prolific Career (So Far)

Learn about the CalArts’ alum’s extensive filmography—as a writer, director, producer, and activist.

Listening, being permeable, porous, and open, and allowing things to affect you.

What was your post-grad journey like in the acting industry?

Well, I think I had a pretty unique experience. I was very fortunate because when I graduated, I graduated with other actors, other young Black actors that were tight. We were the same type and we moved into LA kind of all together, kind of found places near each other. Some of us were roommates with each other and we would actually rush each other’s auditions. So if I had an audition, I would bring my other friends. If they had one, they’d bring us. The casting directors were really tripped out because obviously it’s like if you get a job, then your friend can’t get a job. And if your friend’s gonna get that job, then you can’t get the job. We’re not really in competition with each other for individual roles. And anyway, at least one of us needs to get it because we’re all borrowing money from each other so we can pay rent, right?

Somebody in this crew needs to get it, somebody needs the job. So I think what actually happened, interestingly enough, was that we kind of became the darlings of these casting directors at the time, because we’d all show up as a pack and hang out with them and be goofing around and they would watch us perform. And it was just a whole thing. So that was kind of unique.

Let’s talk about your music and interdisciplinary practices in general. I loved you in Miles Ahead and Talk To Me. How have music and other practices besides acting played a role in your career?

They work with one another. Language is music and a lot of what happens in script analysis. I think when you’re trying to understand not only a character but a story, there’s a lot that has to do with rhythm and there’s a lot that has to do with space, which is a big part of music as well as acting, obviously. Listening, being permeable, porous, and open, and allowing things to affect you. To be in this feedback loop of you affecting it, it affecting you. Finding that sweet spot where those things are just naturally happening. It’s magic when it happens.

You’re still trying to find the truth of the character, the truth in the moment where you fit in the story.

You’ve been in a lot of films or stories that end up having such a wide audience—either cult classics or giant projects. What is it like as an actor being in something like Boogie Nights or something like Ocean’s Eleven that has a cult-classic feel to it, as opposed to something like Marvel films, which have become part of a giant Disney conglomerate?

Every experience is different. We didn’t know that Ocean’s Eleven was gonna be anything when we did it. We were just like, “Oh, this is a cool movie.” And I’ve worked with Steven [Soderbergh] before, and we stayed in touch.

I don’t think we ever know. And the same thing goes for Marvel. Nobody knew that it was gonna do what it did. It’s trickier, obviously, when you’re in something like that as opposed to something like Things Behind the Sun, where you’re very small. There’s no bells and whistles. You’re there for the love of the game. You’re not making any money, and you’re not there for that reason. You’re trying to tell a real specific and important story. Those are the ones that I really love being a part of. It’s sad that those are so hard to find, and no one’s really making them. You have to grind so hard to get those made. It’s fun doing the Marvel stuff, and you get all of the bells and whistles and all the toys and all the cool shit to work with. In those movies, you’re working with a lot of good actors because a lot of strong actors are doing those movies now. At some point, everybody will be in a Marvel project, either on streaming or in the movies. But yes, they’re very different. At the core of it, though, you’re still trying to do the same thing. You’re still trying to find the truth of the character, the truth in the moment where you fit in the story.

You mentioned some of the other films that aren’t as appreciated and valued. As a storyteller, how does advocacy play a role in your work?

As a producer, I’m always trying to support those voices and trying to center those who have not been centered and bring people to the table that, as you say, are often overlooked. As an actor, I’m often trying to find those storylines within that. It’s not just in front of the camera. I have a diversity mandate and have had one long before that became a thing to do. Always trying to make sure that the crews look like the world and that we always have people that are allies. That’s a big part of it. In this post-George Floyd moment, a lot of companies started having these wake-up calls and looking at their practices and realizing, “Wow, we’re not participating in the world in a way that’s conducive to really supporting everyone.” Some have done a 180. What I also feel now is there’s been kind of a blacklash, proceeding back to the normal that it was prior to this. We’re still struggling to find space and create opportunities for people. That’s always been, and not just in my professional life but in my personal life, something that’s important to support.

What movies and music inspired you growing up?

I’ve always been into jazz from a very young age and was listening to the albums that my parents had—Miles Davis; Earth, Wind & Fire; The Spinners; as well as classical albums. My parents were pretty eclectic, and it just continued from there. I loved the artistry. I love listening to people who can really play their instruments and really do their thing. I still have a pretty eclectic palate for the music that I love. So we were listening to everything.

In terms of movies, I was very fortunate to grow up during a golden age: ’70s movies—Godfather, Dog Day Afternoon—you can go down the line. Great filmmakers and great stories. That’s what I grew up on. I really miss that kind of storytelling and that kind of attention to detail and taking your time. The Godfather was on the other day, and you look at the sequence where he finds the horse’s head in his bed, how long it takes to actually get to the horse’s head. They would cut that all out today. We don’t have the attention span. And social media and every aspect of our popular culture has, I believe, just undercut our ability to sit in something, not want to rush to the end. It’s sad because I think we’ve missed out on a lot in the desire to make sure that somebody doesn’t change the channel or make sure that somebody doesn’t get bored.

Is there an actor that inspired you? My dad said you reminded him of Paul Robeson when he first saw you on screen. He was really taken aback by your performance.

Wow, that’s amazing. I mean, a lot of them. The great ones, right? Denzel [Washington], Laurence Fishburne, a great performer. Meryl Streep, Robert De Niro. I think Maggie Gyllenhaal is really good. Gary Oldman is amazing. Tom Hardy.

I do think they’re few and far between, right? There’s not a ton of amazing anythings—doctors, painters, lawyers. It’s not easy to be excellent and stand out in your field. I think that when you do it, it’s because of not just your practice and your study and your focus, but there’s something also that’s nebulous. You can’t necessarily determine what it is that makes someone compelling to watch.

What’s your hope for the future of the industry? You’ve mentioned in past interviews that this is a very different industry than when you started.

I think it cuts both ways right now. It’s a very good time to try to be a part of this because there are so many platforms and there are so many places that are desperate for content and that need performers and actors and creatives, writers. All of these different seats need to be filled for all these different projects. There’s always going to be the crucible that you have to figure out how to get through, but at least there’s more opportunities. Now let me qualify that by saying, as I said earlier, at the same time I see that potentially the window is closing, so it’s high time to do it now. We’re seeing something that never would happen when I came out. Now when people wanna cast you in a movie they are checking how many followers you have on social media, and that could be a determining factor on whether you get a gig or not, which is bananas to me.

To wrap up, I want to thank you for your continued work in theater—I know you still are continuing with things like Strange Loop. Thank you for your work in film, obviously for many reasons. Thank you for your involvement in the community at CalArts specifically, and the work you do on the Board of Trustees. I also want to thank you for supporting marginalized voices.

Hosting Saturday Night Live and choosing to wear the “Protect Trans Kids” shirt was very powerful. It was a proud day for CalArts. It’s such a simple and important thing to say. It’s crazy that it’s radical, but it was. Thank you for that work, and thank you for your time today as well.

Thank you very much. I appreciate that.