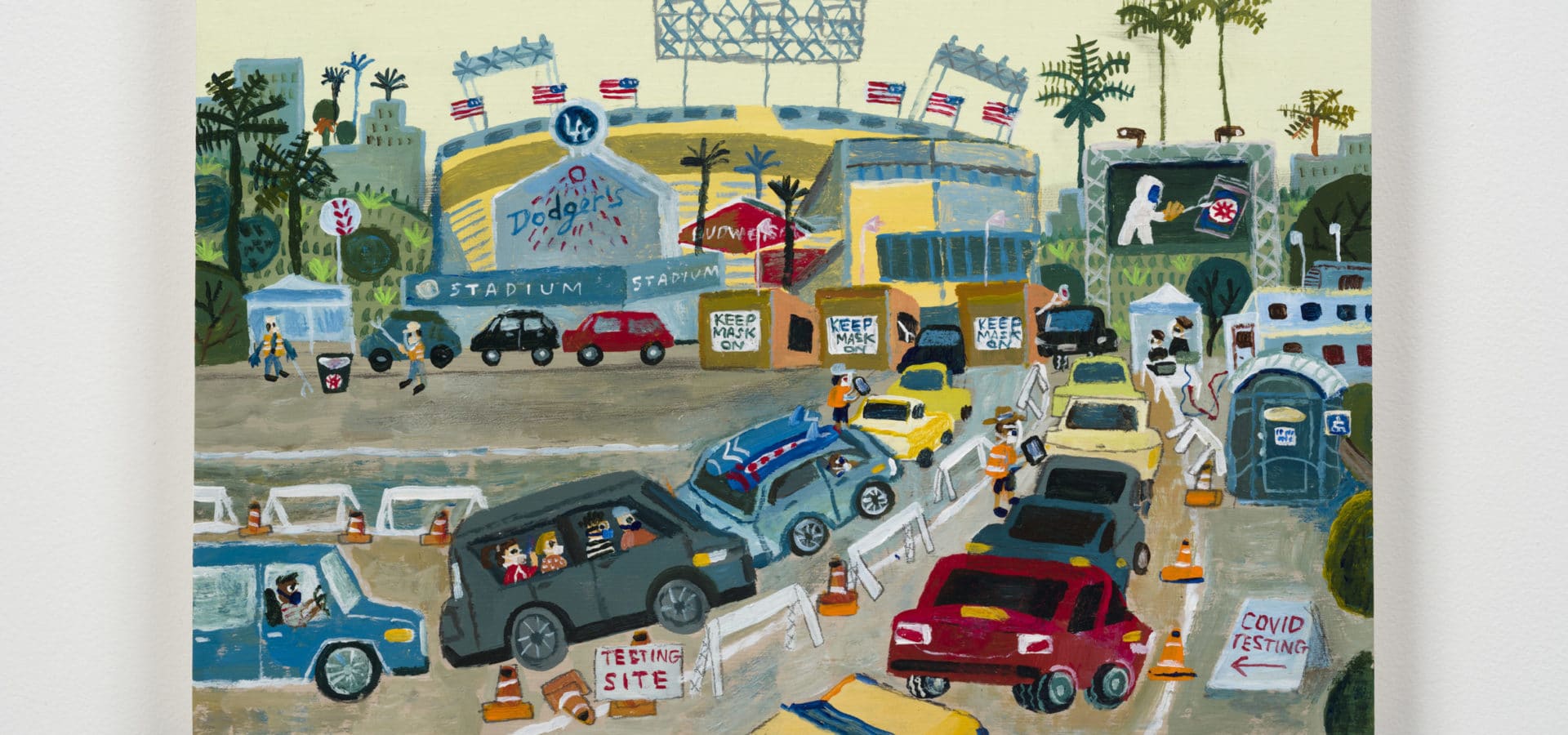

Through dozens of small, colorful paintings, Esther Pearl Watson (Art MFA 12) depicts a rapidly changing world in which the once mundane is juxtaposed against an unprecedented crisis. As the pandemic continued, Watson’s desire to document everyday life in its midst grew stronger.

Watson spent the last year creating a visual diary. It’s a trip to the neighborhood grocery store, but there’s a line outside and the store is completely out of toilet paper. A family goes on a walk in their neighborhood, but they’re all wearing masks. As the days dragged on, Watson felt a growing desire to document this new normal.

“‘At first, I was like, ‘Who am I to tell this story?'” Watson said. “I’m very much aware that it was only my perspective and very limited—a tiny sliver of a story unfolding all over the U.S., all over the world, in very different ways. But after a while, after seeing painting after painting, I feel like all of our stories are important. All of our experiences are little pieces of a collective message that we can all learn from.”

Before the pandemic, Watson was busy. She was teaching full-time at the ArtCenter College of Design in Pasadena, where she received her BFA in 1995 before completing her MFA at CalArts in 2012.

She was also touring across the U.S. with Pop-Up Magazine‘s Winter 2020 show, where performers would tell a short story over live music and visual projections. Watson’s story was about growing up in Texas with her father, an Italian immigrant who built flying saucers the size of cars. He believed the saucers represented the future of travel and that he’d one day sell his designs to Ross Perot or NASA.

Watson started documenting her father’s antics in the early 2000s through folk art-style paintings of shiny saucers, captions emblazoned across the horizons. She’d been inspired by Clara “Aunt Clara” McDonald Williamson’s memory paintings and Grandma Moses’ scenes of rural life, and how they “idealized the hardships of their childhoods.”

“I thought it was really funny, painting [my] dysfunctional childhood from the ’80s using that language,” she said.

Then March 2020 rolled in and Watson’s jet-setting came to a halt, while classes at the ArtCenter were suspended.

“The message came right in the middle of class. I didn’t know what to tell my students or how to keep them calm. I said, ‘Let’s just think of this as spring break,'” she said. “And then in a couple of weeks, we were figuring out how to run a class on Zoom.”

Watson, who co-teaches with her husband, artist Mark Todd, invited work-from-home artists to guest lecture, to assure her students it was still possible to create art without leaving the house.

This was certainly true for Watson. Her household included her husband, her daughter Lili, and her daughter’s boyfriend Keiji, whose family lives in Japan. The young couple had just started school at the ArtCenter themselves, and Watson described the hunkered-down home as “a little art factory.”

Twice a day, morning and night, the family took walks and talked about their days and their work. Watson quickly found her artistic interests changing.

“I heard somebody say that what we’re going through is historic, and if your work is exactly the same as it was before … then you weren’t paying attention. The flying saucer paintings felt like I was shutting the world out and going back to my childhood, but I thought I should actually try to paint what I’m seeing,” Watson said.

What Watson saw was a mix of the banal with the bizarre: panic buying at Smart & Final; homemade masks hung in a tree, free for the taking; neighbors enjoying happy hour on the lawn, distanced six feet apart in a wide circle.

“I tried to capture moments that seem like they’re supposed to be very ordinary, but you would not see if it wasn’t a pandemic,” she said.

Every Sunday, she dropped off care packages to her mother, who lives in a nursing facility, and her sister with autism, who lives in a group home with other adults with disabilities in Altadena. Though Watson couldn’t hug or sometimes even see her relatives, the consistency of the visits and packages brought them peace. And as Watson made her weekly journeys, she noticed the world continuing to change.

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd was murdered by now-convicted Minneapolis Police Officer Derek Chauvin. Protests took hold across the nation, and Watson documented the signs, murals, and banners calling for justice. In June, she painted a skater protest Lili and Keiji attended near the temporarily shuttered Vista Theatre in Los Feliz.

In August and September, wildfires blazed and scattered ash across the city as political signs served as a reminder of the upcoming presidential election. Watson’s paintings contemplated when it would be over. Would the vaccine come? Would Trump be reelected or would Biden win, and what difference would that make? In October, Watson and her daughter volunteered to be poll workers and Watson painted getting tested for the virus at Dodger Stadium.

As clusters of paintings formed on her walls, patterns emerged. It became clear how confused everyone was in the beginning, how anxiety drove people to stock up on bleach and toilet paper, and how the act of documenting daily life gave Watson a sense of control over the uncontrollable.

“Sometimes it was really hard because it’s almost like sticking your face in the middle of the pain,” she said. “But I did feel like I found it cathartic in a way.”

She recalled a point in her life when she went back to Texas to care for her grandparents. Each day, she kept a comic diary limited to nine panels. After her grandmother died, she realized how little time she had left with her grandfather and began recording everything. She searched for meaning in every moment, from her grandfather struggling to stand up from his chair to a group of chickens crossing a road.

“I think the same thing started to happen when I painted these pandemic paintings. I would see sidewalk drawings or birthday party balloons in the front yard, and everything felt like a sign or symbol—that it had meaning or context that I didn’t understand, but might later,” she said.

In November, Watson mounted Safer at Home: Pandemic Paintings at Vielmetter Los Angeles gallery near downtown L.A. Her paintings were interspersed with black banners, the number of U.S. COVID-19 deaths stitched in white. As the numbers grew, the banners doubled in size, dwarfing the paintings they neighbored. By the time the show opened, we’d lost some 250,000 people. (At press time, it’s more than 571,000.)

“It was a deeply moving record of public and political events that she linked to her own personal experience and family events during this time,” Susanne Vielmetter, the gallery’s owner and director, told The Pool. “This was the reason why our audience could intimately relate to this body of work and felt a deep connection to it. Gallery visitors often spent over an hour reading the text on each individual panel and revisiting both the traumatic and the joyful events … helped them process this difficult time.”

Due to social distancing, the gallery admitted just two people inside at a time. Watson watched them take in her work through the storefront window. She made a comment box for guests who wanted to leave her feedback.

“A lot of people said they cried,” she said. “We’ve had to adapt and change, we have to let go of creature comforts, we’ve had to say goodbye. [The show] gave them a space to remember what they had been through, and I think also that’s a testimony to how resilient we can be.”

Watson is still painting. She no longer feels like she has to document everything, but if something strikes her, she picks up her brush. When the pandemic started, Watson’s religious mother predicted she’d be back to church by Easter. Obviously, that didn’t happen. This year, Watson drove past an outdoor Easter service with a sign that read, “Sing inside your hearts.” She painted that.

Watson had some of her newest pandemic paintings in Frieze New York, which ran virtually May 5-9. The entire collection will later appear at the Richmond Center for Visual Arts at Western Michigan University. You can also see Care Package online at Vielmetter. The show includes art created during the pandemic by a group of CalArts grads who’ve kept in touch over the past several years. Care Package features pieces from Watson, Krista Buecking (Art MFA 12), Akina Cox (Art BFA 07; MFA 12), and Claire Nereim (Art MFA 11).