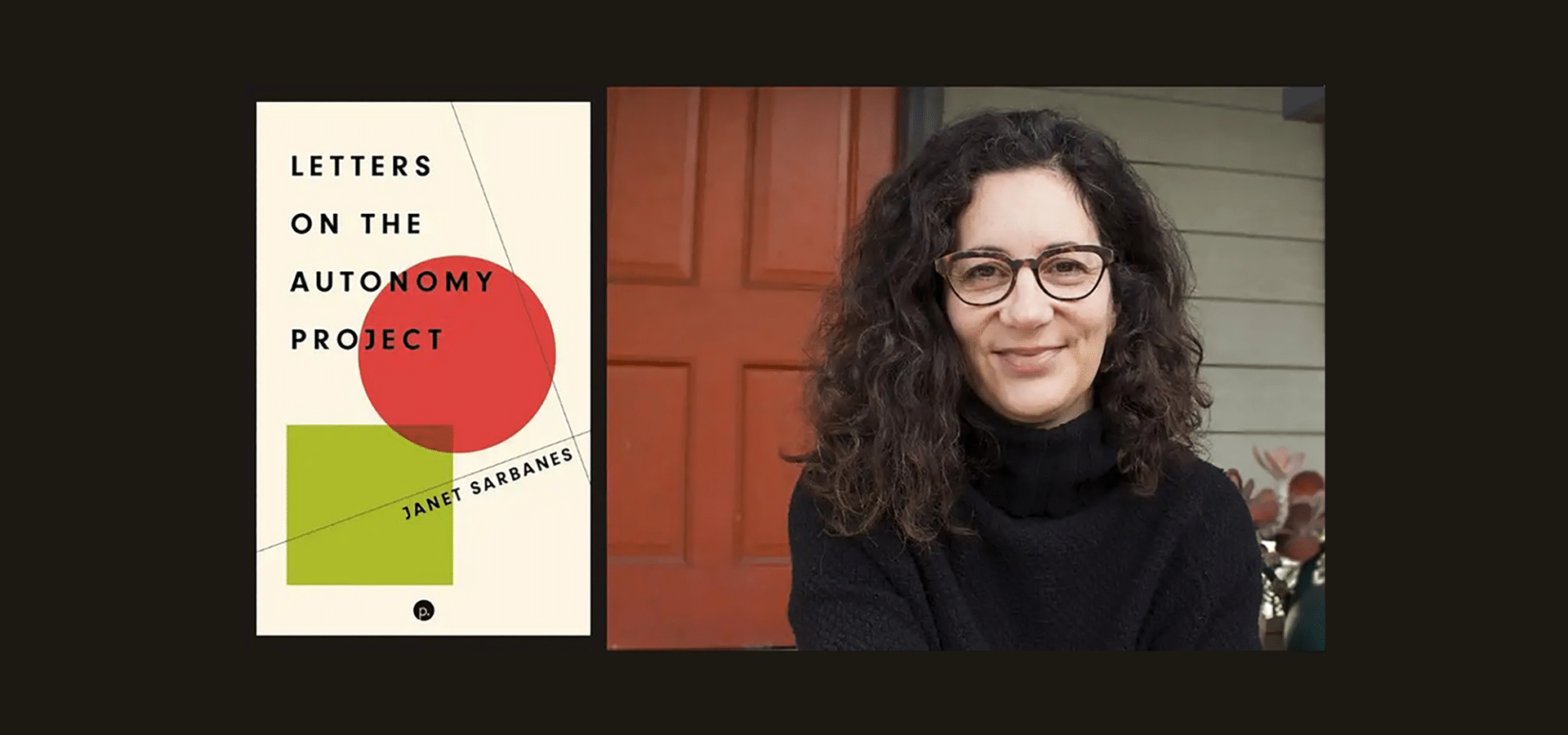

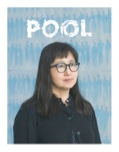

Author Janet Sarbanes, faculty member in the School of Critical Studies, writes open letters to artists, academics, and activists (“Dear A”) in her newest book, Letters on the Autonomy Project (Punctum Books). The subject matter is prescient given the rise of authoritarianism—and loss of autonomy—while at the same time we see renewed struggle against social, political, and economic inequity and injustice.

Rooted in political and aesthetic theory and history, and framed by the thought of Cornelius Castoriadis, Sarbanes’ book examines the possibilities for radical democracy and the radical social imaginary in our era, as well as for art. She asks, how can we understand political and artistic autonomies as linked (rather than diametrically opposed)? What role does pedagogy play in fostering self-determination? “Teaching at CalArts,” Sarbanes observes, “and researching and experiencing its particular legacy of radical pedagogy has definitely influenced my thinking and practice. One of the letters is dedicated to tracing that history.”

In the first open letter, she writes:

One of the central aims of this book is to think through and recalibrate the relationship between art and politics by way of autonomy. Indeed, I believe we cannot face our current crisis of social imagination and political will without a better understanding of autonomy both as a concept and a practice. But just as importantly, this book was conceived in a moment of struggle, and it seeks to contribute to that struggle. Whatever the context of its reading, that is the context of its writing—this is a work of praxis. Some of these letters explore political and aesthetic theories of autonomy; others hearken back to the reignition of the radical social imaginary in the late sixties and early seventies, with special attention paid to Black Radical, Feminist, and Autonomist Marxist approaches to liberation; still others discuss the re-emergence of the radical imaginary in our own time, proof that another world is possible, dear A, every minute of every day.

When asked about the genesis of the book, she responds, “I really wanted to understand the times I was—and we are—living in, which seemed to me to be extraordinary. I was excited by the radical horizon that had been resurrected, the idea that we could change the whole of society, rather than bits and pieces of it here and there, and I felt grateful to be alive in a moment where new solidarities were emerging. I chose the form of the open letter to reflect this fact, to invite the reader to think across struggles, and perhaps most importantly to suggest a radical horizon that expands with each and every demand for self-determination, whether it issues forth from the Black liberation struggle, trans liberation struggle, or workers’ struggle, just a few of the examples considered in the book. I was also struck by how absent art appeared to be from the scene—not the work of individual artists per se but rather the presence of a strong counterculture that could feed these struggles and take them further (the relationship of the Black Arts Movement to the Black Power Movement in the ’60s is instructive here). If we’re living in a time when one of the dominant ideologies of neoliberal capitalism—hyperindividualism–—is coming under real scrutiny, we’re going to have to ask some hard questions about the role of existing art institutions in upholding that ideology, as well as work to create new institutions that link individual and collective creativity in socially and politically liberatory ways.”

Sarbanes, the 2017 recipient of a Creative Capital/Andy Warhol art writer’s grant, has also authored the short story collections Army of One and The Protester Has Been Released. Her art criticism and critical essays have been published in museum catalogs, anthologies, and journals including East of Borneo, Afterall, Popular Music and Society, and the Journal of Utopian Studies. Her essay on Shaker aesthetics and utopian communalism received the Eugenio Battisti prize from the Society for Utopian Studies.