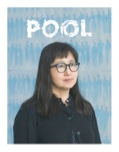

Charmaine Jefferson: In Her Own Words

Charmaine Jefferson, an L.A. native and a pillar of the CalArts community, has worked throughout her career to activate the intersections of art, culture, history, and community. From her own dance career to arts administration, she has been a passionate and committed champion of the artist and arts organizations.

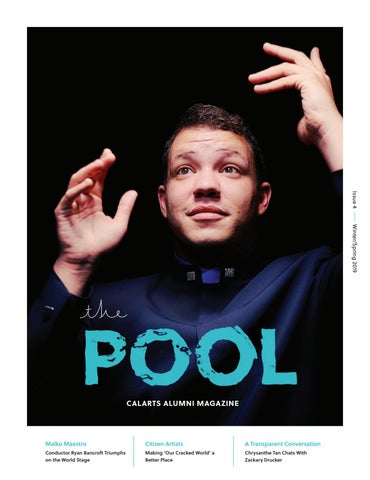

Sitting on the CalArts Board of Trustees for 16 years, she has served on the Finance, Governance and Investment Committees in addition to having Chaired the Academic and Campus Affairs committee; always advocating for the educational and artistic success of students. This past May, Charmaine was elected as the chair of the CalArts Board of Trustees, succeeding Tim Disney, who led the board since 2014.

Throughout my four years at CalArts, and last year as the student trustee, I was fortunate to work with and learn from Charmaine. So it was an absolute pleasure to talk with her recently for The Pool about her life, work, and the journey that led her to her new role at CalArts.

How did you get involved in artistry and specifically dancing?

In 1957, Carolynne Snowden, who had been a very talented hoofer and actress in movies and vaudeville shows, opened the first Black ballet school/studio in the garage of her home. My mother enrolled me at 4 years old because I was always dancing. I was on toe shoes by 11 or 12, but it was not so much about the formality of the art form. I wanted to dance; not stand at the barre, and it was modern dance that gave me the most freedom. I knew I wanted to dance professionally. That’s all I really wanted to do.

While I was in Audubon Junior and Dorsey High Schools, I was able to take modern dance as my gym class. Dorsey had a very robust art program so I also sang in the choir, and we backed up the annual production of a Broadway musical. While still in high school, I started taking classes at the R’Wanda Lewis Afro-American Dance Company. I eventually got to be part of her company. I also took classes at The Inner City Cultural Center, and that gave me a chance to learn from and be a part of a couple of performances with the late great choreographer Donald McKayle. For my Bachelor’s degree in dance, I went to UCLA in 1971. At that time, UCLA had the best dance department in the country—please forgive me, CalArts. In between classes, and becoming a leading member of the Margalit Oved Dance Company, I toured the country. I did pick up work and took every opportunity to go to auditions. If I didn’t get the gig, I treated it like a free class.

In between dancing, I also did some acting and modeling, but the other way I made a living in between the dance gigs was working for a clothing store in Beverly Hills. I worked my way up from the stockroom of Alan Austin’s to assistant to the president. I was good at my job, so they let me come and go to dance and, by osmosis at the store, I also learned accounting and just took all those skills with me, wherever I went. I’m very lucky. I got to live my dream, my very first dream to dance. I feel so blessed that I was able to do so professionally for about eight or nine years. I had no immediate plans beyond that.

Yeah. So that’s my next question, what was beyond that?

I had no plans to ever stop dancing. I was in NYC getting my master’s in Dance Education at New York University in the middle of a performance, when I realized I was thinking about something other than the dance. I went home and applied for two opportunities at the National Endowment for the Arts: an internship and a job as a senior dance program specialist. They didn’t realize it, but one office offered me an internship and another department offered me the job, and I took the job. I had already cried about the idea that I might not dance. I thought, maybe I’ll dance sometimes. Then I realized that wasn’t gonna be possible. I didn’t know how to do it halfway. That’s when I really, really started to understand what kind of an artist I was. I’m either 100 percent in it, or I want to support somebody who’s 100 percent in it. That’s the first time I realized that I was becoming a dance funder and an advocate for presenters, choreographers, and individual artists.

What was the next part of the journey like for you? Post-dancing. That led you to be the Executive Director of the California African American Museum and sit on the CalArts Board of Trustees?

While I worked for the NEA by day, I went to Georgetown Law School at night for 4 years. My grandmother had been the first Black woman to graduate from USC’s Law School, my mother was a legal secretary with her own business, and I had worked temp services in law offices. I had even been president of my high school. It seemed like a natural progression into advocacy.

One of the things that I argued for while I was at the NEA was that all the programs needed to broaden the aesthetic. All they were focused on was ballet and ultra modern. Companies like Alvin Ailey, Dance Theatre of Harlem and Ballet Hispánico were barely getting recognized or seen by panelists. I expanded the Dance Program’s national site visit system to be more inclusive and wrote a paper about broadening the aesthetic. Nowadays, we call it cultural equity, diversity, access, and inclusion, right? What they were considering to be art was too narrow, even for some of the ballet companies, it was too narrow. When I’m having conversations with people about access and inclusion today, I’m less interested in having conversations about diversity and equity because you can get equity if you can get access.

Anyway, one summer, I took a leave of absence from the NEA and did an internship with the law firm of Holland & Knight in Tampa, Florida. I was still single and had only been to Miami years prior dancing, acting, and singing as part of comedian Gabriel Kaplan’s nightclub act. Seven months later, H&K offered me a job in civil litigation and I took it.

While practicing law, I remained committed to supporting the arts. I ended up on state and local panels, selecting grant recipients. When Dance Theatre of Harlem came to Hillsborough County [Florida] to perform, I hosted a reception for them. I wasn’t making a whole lot of money, but I got some of my friends and put some money together because we were gonna make sure that the dance company had a reception.

That’s how I got reacquainted with the amazing Arthur Mitchell [founder of Dance Theatre of Harlem].

A year and a half later, he called me up and said, I want you to come be general manager of Dance Theatre of Harlem. I looked at my law books, my school debt, and thought, ‘How often is the universe gonna send you a once in a lifetime opportunity like this…?!?’….I said ‘YES!’ That’s how I moved from being a funder to dance management and out of an active law practice.

I expected to be in service to Dance Harlem for the rest of my life, but three years later Dr. Mary Schmidt Campbell, then the executive director of the Studio Museum in Harlem was being appointed the commissioner of New York City’s Department of Cultural Affairs by the mayor. She wanted to bring in her own deputy and she recruited me. So each job progressively served the next. Cultural Affairs utilized my management skills, had me serving ex-officio on the boards of the Met and Carnegie Hall, while schooling me everyday on how to assess, oversee, and advocate for physical plant expansions for everything from zoos and gardens to science centers, theaters, performance studios, and public art.

When I left Cultural Affairs, I went back to DTH long enough to oversee the $60 million capital expansion of their school and dance studios and the company’s groundbreaking tour of South Africa at the invitation of Nelson Mandela.

I went on to join the Jacob’s Pillow Board of Directors in Massachusetts, even serving as board treasurer, and in service to other organizations in New York City. Meeting great people, delivering and raising funds every step of the way, I learned I don’t do long-term begging very well. I can ask people maybe once or twice, but after that, we need to get real and I try to respect their space. Instead, I try to stay open to meeting new people who might have something else to offer and get them excited about the missions of the nonprofits I love. That’s why I have so much respect for Advancement teams. They do the lift for all of us.

Fast forward, I went on to be Vice President of Business Affairs for dePasse Entertainment handling film and television deal negotiations, and even stepped back into producing art/entertainment-making as director of Show Development for Disney Entertainment Productions at the Resort and in the Amusement Parks. I wasn’t thinking about being on another board…and then in 2003, I was recruited to head the California African American Museum and its Foundation. CAAM was a life-changing experience…increasing exhibitions, attendance, creating collaborations, producing live Target Sundays at CAAM programs, and performances every month with a brilliant team.

In 2006, I even had the chance to bring then-Senator Barack Obama to CAAM (the morning before he first announced his run for president of the United States) to talk and sign his book for more than 1,000 guests. That was the same year that former CalArts President Steve Lavine, who I had known since my NEA days, and former Trustee Aileen Adams asked me to join the board of CalArts. The first thing I said to them was, ‘If I am on the board I will always give something, but I don’t have big money. Why are you asking me?’ They said they wanted someone on the board who understands management, how the board works, and who can advocate for the school and practicing artists. Okay, then let’s do it. And that’s how I’ve been on the board in service to CalArts for 16 years.

Now serving as the head of the Board, what do you see for CalArts next?

It is scary every time someone asks me that.

I’m here to serve the institution and to support President Ravi Rajan. The president of CalArts leads and develops the vision for the institution. Right? Sometimes people get that wrong. So if we’re here because we believe in the artists and we believe in art, we need to make sure there’s a place where people can create and experiment and find their best paths. Then we have to keep working at how we make it affordable.

I want to be in a position where we’re doing more to connect students with opportunities, either while they’re in school or when they step out of the school, post-grad. Just saying you got a degree from CalArts is great but it isn’t enough. We have to find ways to give you even more for your buck, more connections, more access. All educational institutions can’t just be educators in concept, we have to be practical implementers.

We also need the alums to know that we need them in this quest. We need them to reach back and mentor, but also help them realize that if they’re doing that, they too are gonna meet more people, and it’s gonna expand their universe. I want the alum to know that CalArts is an ever-growing and evolving place. I’ve seen it. I’ve been around long enough to actually say I have seen it. And it is exciting. It really is.

The next questions I have are questions that you don’t usually get in a traditional interview. I just think they’d be fun.

What is your astrological sign?

Pisces

You’re a Pisces, okay. And then would you consider yourself a minimalist or a maximalist?

Maximalist, bordering on hoarder. How about that!

I love that! What is your go-to album?

[After a lot of deliberation] Roberta Flack’s First Take.

Do you have a favorite fine artist?

Well, I find peace in digging through history, not the way they taught it to you in school, but digging through history in terms of how it explains something, how it connects the dots. I am very proud of being related to the founding father of Black History Week, Dr. Carter G. Woodson (my great grandfather’s nephew), and a family committed to social activism. It’s probably just simply tied to being respectful to my ancestors. You know, looking at a picture one day and then turning around and looking at it again later and seeing something different because I now know more about the person or thing than I did before.

Even if they never become famous or the household name, that person did something. So I like to tell the stories of the little things. Rosa Parks would’ve told you she wasn’t the first Black person to sit down in the front of the bus. If we don’t say it out loud, it’s as if it was only Rosa Parks and Harriet Tubman leading the way. No, it was a whole bunch of names you don’t know. I love learning.

It’s our job to know.

So, I love that kind of exploration from artists when they turn that kind of information into art whether through dance, theater, film music or visuals. My uncle John T. Riddle Jr. was a visual artist and he made works that spoke to the issues. I remember being about 9 years old when the three little girls were killed in the bombing of the Birmingham Church. My uncle Johnny made a sculpture about it and I would sit on the floor and stare at the geometric figures. I still own that sculpture.

I love abstracts, but I am especially drawn to work from people like Milton Bowens and Mark Steven Greenfield. The images pictured in their works are people out of history—people or lesser known incidents. Through art, we’re able to show the world that we’re more than just the one or two heroes or moments in history regularly acknowledged.

Even with CalArts, when they went to announce that I was taking this role, I told them, please don’t say I’m the first woman, because I’m not. The original founder of our Institute, Mrs. Nelbert Chouinard, was a woman, and Mrs. Richard R. (Lula) Van Hagen was Board Chair/President when the Chouinard Art Institute and Los Angeles Conservatory of Music were merged to become the California Institute of the Arts. Remembrance is important. Language is important. Context is important.

One news outlet produced an article and it had a big headline that I had “replaced” Tim Disney. Conscious of my skin color and the modesty of my pocket book, I had been very careful and told everyone to make sure that we don’t use that kind of language, but a newspaper picked up the story, and crafted the title of their report using this narrow messaging as their opening approach. It wasn’t our team’s fault, and I was grateful for the coverage, still I got everybody on the phone, including Tim Disney, to talk about why such language posed a problem. The article came out like two days after that man killed those innocent Black people in Buffalo in the name of some ‘White Replacement Theory.’ I said, I didn’t replace Tim. I succeeded him because his term was over. If we’re going to practice cultural competency, this is where language for people of color matters. I asked everyone to get in my skin. Somebody just killed a whole bunch of Black people using the language of white replacement. I can’t come along with no money, Black, and female, and ‘replace’ Tim, his shoes, or his family’s generous money, but I can pick up and expand upon the great work that he did as our former Chair.

That’s the kind of carefulness that I’m trying to bring to this gig—not for my sake, but it’s what CalArts and every other person behind me in that school deserves—which is to uplift what they are able to bring to the table. It was interesting because I was nervous about saying it, but once I said it, I could hear everyone on the call go, ‘Oh, I hadn’t thought about it that way.’ I said, ‘I know because you don’t have to live this on a daily basis. We live this on a daily basis. We train our kids how to survive this stuff. It’s what we pay attention to, the temperature of the room.’ So, full circle is when I can make nuance, and connect dots, then I find my peace, and a way to make a difference.

It was really beautiful to be in the room when you were named chair of the board, for me personally. A predominantly white arts education can be so daunting and feel isolating at times. Having the power to be in that room and be involved in electing you was one of my happiest days at CalArts.

Trust me when they asked me to do it, I was beyond honored and especially grateful for the Trustees’ support, but I did say, ‘Let me think about this for a minute.’ Here’s all the things that can go wrong with this, because this is gonna be a test. Everybody is having their conversations about cultural competency and inclusion and access, and I go, ‘Okay, this is a true test of the application of all that talk.’ I want CalArts to be a leader, not just in turning out amazing artists, which it has already been doing, but a leader in voicing and advocating all that the arts stand for throughout society. We already understand and know this at CalArts. We preach this gospel to ourselves every day. We just need to talk about it in additional ways and get it out there. I think that’s part of what my job is. It’s gonna take the village of CalArts, the alum, the students, their parents, The Trustees, the beneficiaries of what a CalArts education does. That includes the gallery owners and all of that to say, yes, we need to keep investing in CalArts because at the end of the day, the value of what CalArts puts out there is fantastic.

We need to reconnect.

Yep, absolutely. So that’s my, that’s my quest. My new job.

Your newest job.

My new unpaid job. You’d be surprised how many people go, oh, you got this new position at CalArts. I go, it’s not a job. I’m a volunteer trustee and I am happy to do it.