When done in earnest, protests generally aren’t seen as a place for fashion. But Camille Benda, author of the book Dressing the Resistance: The Visual Language of Protest Through History, might beg to differ. It examines the role clothes play in activism, from what’s worn to what is not.

Benda, CalArts’ head of the Costume Design program, told The Pool she was moved to write a book on protest dress by “CalArts’ overall ethos of citizen artists—or, artists who are engaged in society and who help create the world around us and reflect [it] back at society.”

“I think I became inspired because I saw that the arts can really be a catalyst for social change,” she said. “And it got me thinking about clothes. Dress is so close to us as human beings and tells so many stories that it was a perfect way to talk about activism and resistance.”

There are myriad diverse examples in the book—Benda said she crammed in as many as she could—and the definition of fashion is broad.

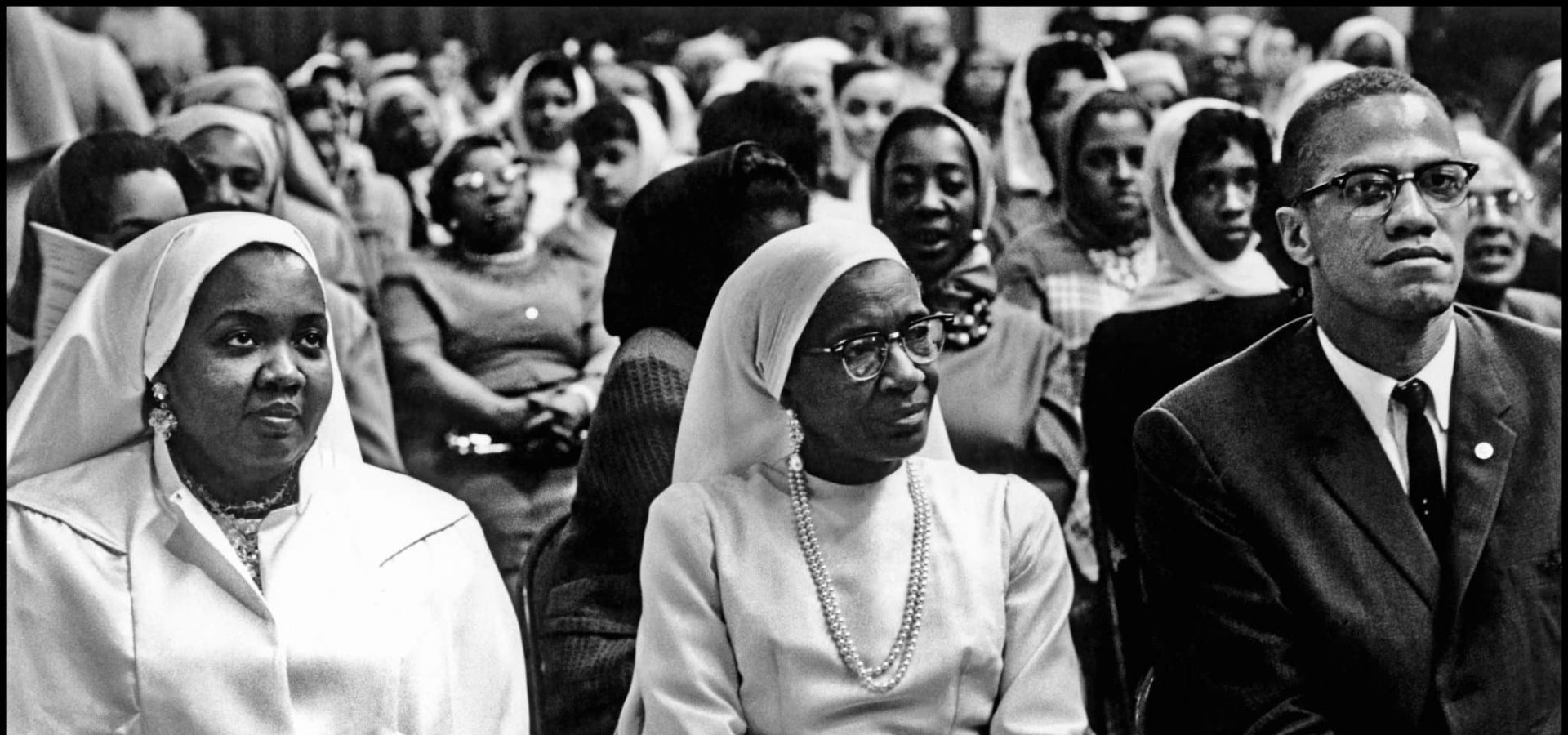

One of her favorite sections talks about how Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X wore tailored shirts and suits as a way to “elevate the status of Black men and [show] how they could wear the same garments as the president of the United States.”

Another features musician, artist, and activist Madame Gandhi, who, in 2015, ran the London Marathon while free bleeding. Gandhi would later explain that she started her period just before the race began and decided to not use a tampon.

“I ran with blood dripping down my legs for sisters who don’t have access to tampons and sisters who, despite cramping and pain, hide it away and pretend like it doesn’t exist. I ran to say, it does exist, and we overcome it every day,” Gandhi wrote.

For Benda, Gandhi’s blood-stained apparel “shows how much clothing is interconnected with the body and how we portray ourselves”—which can also include choosing to wear nothing at all.

Russian artist Petr Pavlensky has used what Benda calls “extreme nudity” in protesting. He once nailed his scrotum to the pavement in front of Lenin’s Mausoleum at Red Square in Moscow as a “metaphor of apathy, political indifference, and fatalism of Russian society,” and sewed his mouth shut to protest the arrest of members of Russian feminist activist and art performance group, Pussy Riot.

“Even using that technique of sewing, that we use for clothes, to sew your mouth shut is extremely powerful,” Benda said.

In the more recent demonstrations against Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, Benda points to protestors who’ve taken to the streets in blue and yellow, the color of Ukraine’s flag.

“One of the interesting things about protests is that if you’re using a color … it’s a very immediate and accessible way of protesting,” she said. “Anyone can pick up a simple piece of color, wrap it around their wrist, or paint it on their face.”

She’s also fascinated by the sartorial choices of Ukrainian president Volodymyr Zelenskyy, who doesn’t wear his flag’s colors. He is instead frequently seen in drab tones, but not traditional military garb.

“Instead of creating a militarized or official uniform, he’s created this sort of slightly relaxed persona of somebody ready to get in with the people and ready to help out at any time,” she said. “T-shirts, fleeces, tactical pants—everything is very utilitarian.”

But the most “poignant visual symbol,” for Benda, is the flower crown, which ties back to traditional Eastern European dress.

In 2016, Vogue reported on the flower headdresses—known as vinoks—in 2016, and how the Ukrainian symbol had become near-ubiquitous in Kyiv fashion retailers following the 2014 revolution and a surge in national pride.

Benda wore a flower crown to her wedding, due to her own Eastern European background. Her family escaped what was then Czechoslovakia in 1968, the year the Soviet Union invaded, ultimately landing in Seattle.

There, Benda developed an interest in sewing and vintage fashions at a young age, often making her own clothes.

“If I were going on a date, I would suddenly, in the middle of the afternoon, decide I needed to make a new outfit,” she recalled.

Benda did not immediately consider turning her hobby into a job. Among her family, “there wasn’t really an understanding that you could make a career as an artist.” Only her uncle, a musician, worked in the arts and was “considered a bit of an outlier.”

So when she enrolled at the University of Washington, she chose classical studies and Slavic languages as her focus. Her studies had little to do with clothing, but they did instill an appreciation of history—key to her future work in costume design.

Toward the end of her degree, she wandered into the school’s costume shop and began asking questions. When she found out they didn’t have anyone to design costumes for a student play, she volunteered.

“That was my first foray into it, and then I was hooked.”

After graduation, she took several drawing classes and worked on fringe theater productions in Seattle before completing a one-year master’s program at the Courtauld Institute in London in the History of Dress and Textiles and her master’s in Theater Design at Yale.

[CalArts] has been crucial to understanding myself as an artist and also being able to share what I’ve learned over the past 30 years

In 2002, she returned to London, having met her husband-to-be while at Courtauld, where she spent several years working in film.

Benda’s decision to move to California in 2013 had nothing to do with her career, but the weather. She’d spent years under the gray skies of Seattle and London and was ready for some sun.

Upon arriving in Los Angeles, Benda joined The Costume Designers Guild Local 892, where she met CalArts alum E.B. Brooks (Theater MFA 07), who introduced her to Ellen McCartney, CalArts’ director of Experience Design and Production.

Benda pitched McCartney a course connecting costume design and animation, and has now been teaching at the school for five years.

Having not come from a teaching background, Benda’s classroom approach is one that combines the very practical—i.e., what is a career in costume design—and the dramaturgical, focusing on world-building and costume as part of character.

“So, it’s not really thinking about costume as a piece of clothing somewhere that someone designs, but as integral as props and production design and lighting,” she said.

Benda finds world-building can happen as much in contemporary dress as in period pieces. Her work has included the punk rock stylings of Pelican Blood (2010), a drama about troubled bird watchers, and The Last Manhunt, a forthcoming drama set in 1909 following two Chemehuevi seeking justice for their murdered tribal leader.

Her most recent project, Bad Sisters, is a Dublin-set dark comedy premiering on Apple TV+ in August. For research, Benda spent time in the area of Dublin where the fictional sisters grew up, observing street fashion and working with brands to create a world for every character. To further ground the eponymous sisters, Benda and Irish jeweler Slim Barrett made them necklaces. Each featured a charm to act as a symbol for the character, as though each had plucked the charm that resonated most from their late mother’s bracelet.

As Benda’s world continues to include both her own work as a costume designer and author and her role as a teacher, she finds CalArts remains a key part of it all.

Follow Benda and @dressingtheresistance on Instagram for additional information about costume design.