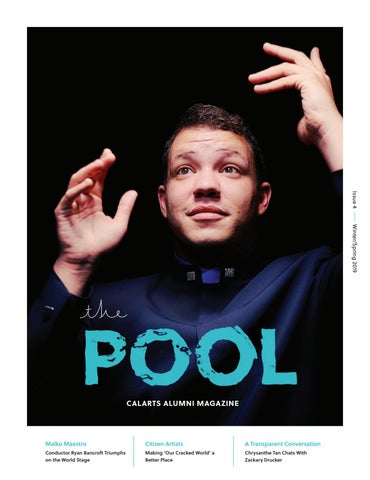

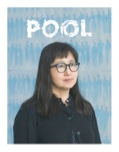

Poet, translator, and CalArts alum Don Mee Choi (Art BFA 84, MFA 86) received a call earlier this year that changed her life. On the line was the MacArthur Foundation, naming Choi one of the 25 MacArthur Fellows for 2021, an annual class of creative and inspiring individuals selected from all fields. Known colloquially as the “MacArthur genius grants,” the recipients are writers and artists, scientists and teachers, entrepreneurs, or from other disciplines who use the $625,000 stipend to further their current work or explore new directions.

Born in Seoul, South Korea, Choi’s work as a poet confronts the effects of military violence and US imperial legacies on the Korean Peninsula. Likewise, her poetry collections challenge the norms of verse, often experimenting with and pushing boundaries—text is interspersed between visuals and drawings, archival materials, and handwritten documents. Many of the materials come from the artist’s photojournalist father who covered uprisings and warzones in Korea and Vietnam.

Choi’s latest collection DMZ Colony (Wave Books, 2020), which won the National Book Award for Poetry last year, chronicles the artist’s return to Korea while simultaneously documenting the brutality and lifting up the voices of survivors of the Korean War. Hardly War (Wave Books, 2016) is a hybridized poetry collection, memoir, and opera libretto that explores her paternal relationship as well as history heritage often steeped in horror.

Additional collections include The Morning News Is Exciting (2010) and several chapbooks. She has translated a number of books from Korean to English with a particular focus on the works of Kim Hyesoon, an influential feminist poet who challenges the expectations of traditional lyric poetry in Korea.

For The Pool interview, we conducted a Q&A with Choi via email as she is currently teaching in Germany as the Picador Professor for Literature at the University of Leipzig. The questions touched upon her work, her time at CalArts, and the concept of “genius.”

You studied art at CalArts, earning both a BFA and MFA. How did that background lead you to become a poet and translator?

I started writing some poems when I began making 8mm and 16mm films. I wanted to add a voice-over to the films, and what I wrote turned out to be poems. I also took literature classes taught by Jo Berryman (Critical Studies) and went to all the great poetry readings she curated. I was able to read and hear May Sarton, Denise Levertov, Octavio Paz, Joseph Brodsky, and Czesław Miłosz. I didn’t know at the time that I would pursue writing poetry, but it emerged more strongly as I was translating contemporary Korean women’s poetry. Translation is what allowed me to find my language—my particular English. I also discovered that a book could work as an artistic medium. Like film, it takes place in time (time set by each reader), and it can be highly visual as well. I also like the fact that a book can be a beautiful, yet very affordable object.

Was there a particular poem/poet/writer that sparked your desire to write?

I was always drawn to sensing music or rhythm in poetry as well as in prose. Whenever I spliced/glued my 8mm or 16mm films, I felt as if I was writing. Arranging and juxtaposing images was like working with blocks of language, sentences, or words.

I read in an article that you arrived in the US alone on a student visa in 1981, from Hong Kong to LA, crying all the way. Do you recall what it was like for you to land in Valencia/Santa Clarita—a place so different from Hong Kong and Seoul?

I had never been on a freeway before, so that was a whole new experience for me. The landscape and vegetation were also drastically different. As soon as I checked into my dorm room, I became unsettled by the waves of swishing sounds from my window, facing Magic Mountain with giant roller coasters. (To be honest, I had no idea what those white curvy structures were.) I couldn’t understand why I was hearing the ocean when it was all desert outside. After staring out the window and watching the trucks and cars go by for a few days, I realized that the sound of the ocean was coming from the freeway. This memory still haunts me.

While studying at CalArts, did you have a mentor or faculty member that particularly influenced you?

Faculty members Douglas Huebler and Jeremy Gilbert-Rolfe both influenced me a great deal. I had absolutely no confidence in myself. Yet somehow, they believed in me and thought I had potential as an artist. I still see them in my dreams from time to time. I was also lucky to have very kind friends, John Carson and Darcy Huebler, who patiently mentored me.

Your books, including the National Book Award winner DMZ Colony, are filled with poems, prose, photos, illustrations, and textual and graphic design elements (e.g., “Ruoy Ycnellecxe”) that challenge the reader. When and why did you begin to challenge the notion and conventions of poetry?

About 20 years ago, when I first began translating Kim Hyesoon—an incredible, prominent South Korean poet—she told me that she had no mother tongue because the language she is expected to write in is regulated and prescribed by men. And therefore, she had to seek and invent her own language for her poetry. And this helped me to think about my own tongue, which I think of as an expelled tongue. Expelled because my family had to leave South Korea to escape the brutal military dictatorship backed by the US. For me, challenging the notion and conventions of poetry is inseparable from challenging the notion and conventions of imperial/neocolonial language and narratives that still shape Korea’s contemporary history.

I know the MacArthur Foundation doesn’t formally use the word “genius” when referring to its grant, but you and your class of fellows are impressive in your respective fields (so it fits!). Is a “genius” born or nurtured?

To be nurtured as a “genius” means you are born into or have access to a certain amount of privilege—privilege to create, which means you have stable housing, health care, time, etc. Even my freeway phobia is born out of privilege, relatively speaking. I wasn’t trapped in a sweatshop somewhere in Seoul to support my family and pay tuition for my male siblings. I was able to land in the US with a “real” student visa. The day I arrived at LAX, I watched a Korean family being held and harassed by a customs officer because they had supposedly entered the country with “fake” visas. I felt like crying again, but I managed to keep myself together. I couldn’t let all the paints, brushes, and pencils in my bag go to waste. That family probably had to sell everything they owned in Korea to buy their tickets and obtain “fake visas.” I don’t think we can say who is a “genius,” really. Structural inequities—globally and nationally—definitely propel and nurture the idea of a “genius.” I became really terrified after I heard from the MacArthur Foundation. I felt terrified that I would finally get busted for being a fake in this country.

CalArtian MacArthur Fellows

Poet and translator Don Mee Choi is the latest CalArtian to be awarded the prestigious MacArthur Fellowship, colloquially known as the “genius grants.” Here’s a look at past grantees.

Bill Irwin | MacArthur Fellow 1984

In 1984, performer, director, playwright, and clown Bill Irwin (Theater 72) was the first performance artist to be awarded the five-year MacArthur Fellowship, lauded in the Theatrical Arts category for “a special interest in bringing traditional vaudeville and silent film imagery to contemporary comedic theater work.” Called a “clown with a mission” by The New York Times, Irwin began his stage career as a vaudeville-style performer, attending CalArts, Oberlin, and the Ringling Brothers and Barnum & Bailey Clown College before founding the Pickle Family Circus in San Francisco, which played a major role in the 1970s American circus revival. The “master interpreter of Samuel Beckett” (Los Angeles Times) went on to an illustrious career on stage, awarded the National Endowment for the Arts Choreographer’s Fellowship in 1981 and 1983, named a Guggenheim Fellow in 1984, a New York Drama Critics Circle Special Citation in 1988, and an Outer Critics Circle Award and Drama Desk Award in 1989, among other honors. In 2005, he won the Tony Award for Best Actor in a Play for his role in the critically acclaimed revival of Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?. On screen, he is known for memorable turns in films such as Interstellar and Rachel Getting Married, as well as numerous roles on television, including Mr. Noodle on Sesame Street’s Elmo’s World.

Guillermo Gómez-Peña | MacArthur Fellow 1991

San Francisco-based performance artist, playwright, activist, and CalArtian Guillermo Gómez-Peña (Art BFA 83, MFA 85) was awarded a MacArthur Foundation genius grant in 1991. Recognized in the area of Theatrical Arts for his work promoting intercultural dialogue and understanding, the MacArthur Foundation explains that “Gómez-Peña uses the US-Mexico border as a metaphor for the borders within our identities as defined by race, sex, class, and nationality.” Born in Mexico City, his work—including performance, installation, video and audio art, bilingual texts, journalism, digital technology, and 21 books—have contributed to the debates on cultural, generational, and gender diversity; border culture and mythologies; and US-Mexico relations. In 1994, he founded his longest-standing project, the influential and transdisciplinary performance art troupe, La Pocha Nostra, of which he serves as artistic director. In addition to being a MacArthur Fellow, he is a Guggenheim Fellow and a USA Artists Fellow, a Bessie and American Book Award winner, and currently a Patron for the London-based Live Art Development Agency and a Senior Fellow in the Hemispheric Institute of Performance and Politics at NYU. He is a regular contributor to newspapers and magazines in the US, Mexico, and Europe, including The Drama Review (NYU-MIT), the Performance Art Week Journal of the Venice Biennale, and emisférica (NYU). Gómez-Peña’s artwork has been presented at over 1,000 venues both nationally and internationally, including the Tate Modern, London; the House of World Cultures, Berlin; and the Chopo Museum, Mexico City.

Vija Celmins | MacArthur Fellow 1998

In 1998, painter, sculptor, and former CalArts faculty member Vija Celmins was awarded a MacArthur Foundation genius grant in 2D and 3D Visual Art for her realistic and abstract creations. Born in Latvia and raised in Indiana, Celmins is best known for photorealistic paintings and drawings of natural imagery, including ocean waves, desert floors, spiderwebs, and night skies. Her paintings, sculptures, drawings, and prints depict scenes that are too vast to be fixed in the mind’s eye, yet demonstrate a meticulous attention to physical detail with subtle abstract variations. As the MacArthur Foundation notes, “Regardless of medium or subject, her intensity of observation and her rigorous transformation of physical reality into art (oscillating between concrete and abstract presentations) yield a powerful body of work.” Working between New York and California, she has been the subject of over 40 solo exhibitions since 1965, with major retrospectives at the Museum of Modern Art; Whitney Museum of American Art; Los Angeles County Museum of Art; San Francisco Museum of Modern Art; Institute of Contemporary Arts, London; and the Centre Pompidou, Paris. Celmins taught at CalArts from 1966 to 1977 and, in 1994, was awarded an honorary Doctor of Arts degree for her extraordinary contributions to contemporary arts and culture, while representing the bold innovation and visionary creativity championed by the Institute.

David Wilson | MacArthur Fellow 2001

Artist, designer, and curator David Wilson (Film/Video MFA 76) was named a MacArthur Fellow in the area of Curation, Collecting, and Conservation in 2001. In 1984, he founded the Museum of Jurassic Technology, a traveling collection for galleries, community centers, and museums, establishing its permanent home in Culver City, California, in 1988. Six years later, Wilson opened a German branch at the Karl Ernst Osthaus-Museum in Hagen, Westphalia, and in 1995, he and the museum were the subject of the book, Mr. Wilson’s Cabinet of Wonder. As the MacArthur Foundation explains, “Through his collection of biological, archaeological, and cultural curiosities in the Museum of Jurassic Technology, Wilson blurs the distinctions among museum, mausoleum, and library. His installations question what museums are, mean, and do.” Once called “Los Angeles’ Strangest Museum” by Smithsonian Magazine, the Museum of Jurassic Technology is now open by appointment only. Wilson started making 16mm films while attending Michigan’s Kalamazoo College, before moving to California to study Experimental Animation at CalArts. His films from the 1970s and ’80s explore the act of perception, and he has produced commercials, trailers, special effects, industrial films, and six independent films, most recently under the auspices of the Museum in collaboration with Kabinet, an arts and science-based cultural institution located in St. Petersburg, Russia. In 1977, Wilson, along with a group of Los Angeles filmmakers, co-founded Independent Film Oasis, a screening series for avant-garde film. Also in 2001, he was awarded the Creative Capital Moving Image Award and, in 2015, was awarded an honorary Doctor of Arts degree by CalArts.

Mark Bradford | MacArthur Fellow 2009

Inducted as a MacArthur Fellow in 2D Visual Art with the class of 2009, mixed media artist and native Angeleno Mark Bradford received both his BFA (Art 95) and MFA (Art 97) from CalArts. “Incorporating ephemera from urban environments into richly textured, abstract compositions that evoke a multitude of metaphors,” as noted by the MacArthur Foundation, Bradford is best known for his massive-scale abstract paintings and assemblage collages created out of paper, signage, and other materials, often collected from his own neighborhood in South Central Los Angeles. Through layered complexity, Bradford’s work explores the effects of social and political structures on marginalized and vulnerable populations. Building upon those ideas, Bradford makes social engagement an essential part of his practice, bringing contemporary art into communities with limited access to cultural institutions. His work has appeared in exhibitions at the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Studio Museum in Harlem, the Los Angeles County Museum of Art, the Hammer Museum, and the Museum of Modern Art, among many others. Bradford was awarded the US State Department Medal of Arts in 2015 and represented the US in the 2017 Venice Biennale. Earlier this year, he was elected to the American Academy of Arts and Letters.

Carrie Mae Weems | MacArthur Fellow 2013

Considered one of the most influential American artists working today, photographer, filmmaker, activist, and CalArts alumna Carrie Mae Weems (Art BFA 81) was named a MacArthur Fellow in 2013 in the category of Photography and Moving Image. Prolific in practice, Weems was honored for her work “examining the legacy of African American identity, class, and culture in cinema verité–style works that incorporate elements of folklore, multimedia collage, and experimental printing methods.” Since receiving her first camera in 1973, she has developed a massive body of work comprising photography, video, installation, text, audio, fabric, digital images, and more. Known for her tender and evocative depictions of families, children, and individuals in intimate settings, Weems both documents and deciphers family, culture, class, gender, and the consequences of power, as well as the ongoing struggle for racial equality in America. As an activist, Weems helped found Operation: Activate, a public art project calling for an end to gun violence through billboard advertisements and matchbooks, and The Institute of Sound + Style, a summer program that offers teens from low-income families the chance to learn about music production and fashion. She has exhibited both nationally and internationally and is represented in collections around the world, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art; The Museum of Fine Arts, Houston; the Museum of Modern Art; the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles; and The Tate Modern.

Maggie Nelson | MacArthur Fellow 2016

Named a MacArthur Fellow as part of the class of 2016, writer Maggie Nelson is the former chair of the Creative Writing Program in the CalArts School of Critical Studies. Recognized in the area of Fiction and Nonfiction Writing, Nelson was honored for “forging a new mode of nonfiction that transcends the divide between the personal and the intellectual and renders pressing issues of our time into portraits of day-to-day lived experience.” The author of five nonfiction books and four works of poetry, her work explores art, feminism, queerness, sexual violence, the history of the avant-garde, aesthetic theory, and philosophy. She has been the recipient of a Guggenheim Fellowship in Nonfiction (2010), a National Endowment for the Arts Literature Fellowship in Poetry (2011), an Innovative Literature Fellowship from Creative Capital (2012), and an Arts Writers Fellowship from the Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts (2007). In 2015, The Guardian called Nelson “one of the most electrifying writers at work in America today,” the same year her New York Times bestseller, The Argonauts, won a National Book Critics Circle Award. Her most recent book, a work of cultural criticism titled On Freedom: Four Songs of Care and Constraint, was published in September 2021. Currently a professor of English at USC, Nelson will serve as the 2022 CalArts MA Aesthetics and Politics Theorist in Residence.