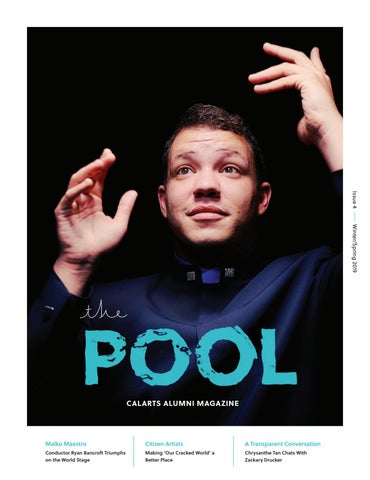

Winning a Tony is something few people accomplish. Winning a Tony after Broadway was shut down amid a pandemic is even more unusual, but that’s how it happened for Justin Townsend (Theater MFA 03) at the 74th Annual Tony Awards.

The ceremony, which had been delayed for several months, recognized the 2019-2020 shows that had opened before shutdowns. Townsend won his first Tony for Best Lighting Design of a Musical for Moulin Rouge!, though he’d also been nominated in the same category for Jagged Little Pill.

Townsend noted the double-nom was “bittersweet”—winning is exciting, but that meant his other team didn’t win. He told The Pool he felt grateful “to be able to paint pictures with lights” for a living.

There was also a sense of relief, a reassurance that theater would eventually—as it always has—go on. In fact, it already had. Townsend was calling from London, where he was staging the West End production of Moulin Rouge!

Townsend, now a renowned lighting designer and an associate professor in Brooklyn College’s Department of Theater, said he initially “tried to do anything besides work in the theater business.” But after dabbling in various subjects, he realized lighting was his passion, which his grades and attendance records reflected.

Townsend said it makes sense when you consider his mother was a painter, his father was an engineer, and his stepmother worked in finance.

“[Lighting design] is a triangulation of all those efforts—both a visual sensibility of sculpting space and time with light but also the mathematical and economic rigor of a kinetic machine that exists in conversation with a performance.”

In 1997, he earned his BA in Theater at the University of Massachusetts in Amherst, some 80 miles from his hometown of Andover. He quickly racked up gigs as a sound and lighting designer, but quantity wasn’t necessarily quality.

“I was hustling. And I found that when I was hustling, I was just making terrible art,” he said.

That changed a few years later when he became lighting designer Christopher Akerlind’s assistant. Akerlind was working on an adaptation of the seldom-staged Shakespeare play, King John, in New York.

“I had never seen anything so stunning,” Townsend recalled of the 2000 production. “It was an inspirational moment of, ‘Oh, it could be like that. We could make work that way.'”

Akerlind was also CalArts’ head of Lighting Design at the time. He’d been introduced to Townsend by a mutual friend, who told Akerlind that Townsend was looking to work with a designer who could provide a “provocative experience.”

“So, we had an interview and I was immediately struck by his charm,” Akerlind recalled. “And he was smart as a whip. There were things he said that he had observed [in my work] that indicated to me he had a really good eye.”

Townsend eventually told Akerlind he’d like to attend CalArts, and three months later, he was driving across the country to California.

For Townsend, CalArts was a turning point, a place full of “passionate, curious” people. He counts Theater faculty Christopher Barreca, Mona Heinze, Travis Preston, and Erik Ehn as key figures in his development as an artist.

“[Ehn’s] language still sizzles and pops, but one of the things I still hold onto is the idea [that] ‘theater is what you get away with on stage,'” Townsend said. “It’s a lovely gift of a sentence because it opens the door to what actually is possible instead of what we know.”

For Akerlind, Townsend was a fun student who livened up his classes. Akerlind’s own mentor, Yale School of Drama professor and MacArthur Fellow Jennifer Tipton, trained him to think about theater holistically, to not just get wrapped up in lighting a stage, but to tell a story, which Akerlind finds true of Townsend’s work as well.

“Light is such an interesting medium because you can’t see it, it disappears, it’s ephemeral. Light simply doesn’t exist at the end of a production,” Akerlind said. “I think that’s part of why it lends itself to a kind of deep thinking about the relationship between light and music and story. That’s fun to teach and it’s really fun to teach when you’ve got a student like Justin who absorbs but also reflects the ideas back into his own language and work.”

After completing his MFA in 2003, Townsend returned to New York City. He and a group of friends rented an apartment in Brooklyn where one room served as a studio and home base for other CalArts grads, including scenic designer Efren Delgadillo; lighting designer Brian Lilienthal; David Taylor, director of Production at Jazz at the Lincoln Center; stage designer Peter Ksander; lighting designer Miranda Hardy; and scenic designer Matt McAdon. (He also worked with CalArts grad and Billions star Condola Rashād when she starred in Broadway’s St. Joan in 2018.)

Townsend also found the interesting work he’d been craving.

In 2010, he worked with the Yale Symphony Orchestra and Yale scholar Anna Gawboy to stage Russian composer Alexander Scriabin’s Prometheus: The Poem of Fire.

When Scriabin wrote the symphony a century earlier, he included parts for a clavier à lumières—or, “color organ” — that would project colored lights with the music. It had never been performed as intended in the composer’s lifetime, leaving the team to interpret Scriabin’s notes.

That same year, Townsend broke onto Broadway with the musical Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson (2010), directed by Alex Timbers who also directed (and won a Tony for) Moulin Rouge!

Townsend wasn’t versed in Broadway’s rules or expectations then but knew he could make great work. So, he let himself see—as Ehn had suggested years prior—what he could get away with on stage. This time, that involved stringing three miles of Christmas lights through the set.

“I’m proud of the exploration of space and specifically, our relationship with labor and creativity. [Bloody Bloody Andrew Jackson] was really handmade as opposed to using a lot of expensive tools,” he said.

With 2016 came American Psycho, The Humans, and Townsend’s first two Tony nominations.

The two couldn’t be more different in tone. American Psycho was a musical based on Bret Easton Ellis’ novel (and Mary Harron’s film) about a vapid serial killer on ’80s Wall Street. It contained murder, mayhem, and strobe-lit club scenes.

The Humans was a play about a family falling apart as it grapples with changes. It was set in a Chinatown duplex, the lights going out around them “like a ghost story,” Townsend said.

Townsend’s ability to customize a lighting plan for each space and situation, no matter how different, is something he credits to his CalArts training.

“It’s in thinking, ‘OK, all things are specific and unique, so how can we point at and celebrate that?’ And so when I do that in my work, it means, ‘Oh, look, we’re going to another space,'” he said.

Moulin Rouge!, Baz Luhrmann’s love story bathed in neon and color, is another space entirely. Townsend compared its excess to Rococo. But what do you “get away with” when nothing is too much?

“The first thing we got away with was the absurd amount of set electrics,” Townsend said.

In addition to traditional lighting equipment, Townsend and his team created installations that came to life within the scenery. How much electric pizazz the audience receives ebbs and flows with the story.

“The first 10 minutes [there’s so much happening] it’s almost like Pop Rocks in your mouth,” Townsend said. But when the cast does the tango “Roxanne,” Townsend employs just simple shafts of light on the performers.

“Then, in the middle of the number, horizontal beams of light come straight out of the audience. It’s exciting, it’s theatrical, it’s being in the room with the performance,” he said.

Surprisingly, however, Broadway isn’t where Townsend feels like he employs his CalArts training the most, despite its massive scale. That’s in the theater work he creates with his wife, director/actor Elena Araoz, also this season’s producing artistic director of Princeton University’s Theater and Music Theater.

“I get to explore space and time in a sculptural way, [which is] really rewarding. It’s simple things, like getting 100 extension cords and squirrelly little red fluorescent light bulbs and making a nest overhead the performance. That somehow feels the most elegant,” he said.

The couple lives in Montclair, New Jersey, with their two children, where their neighbor was thrilled to announce Townsend’s Tony win to the local paper.