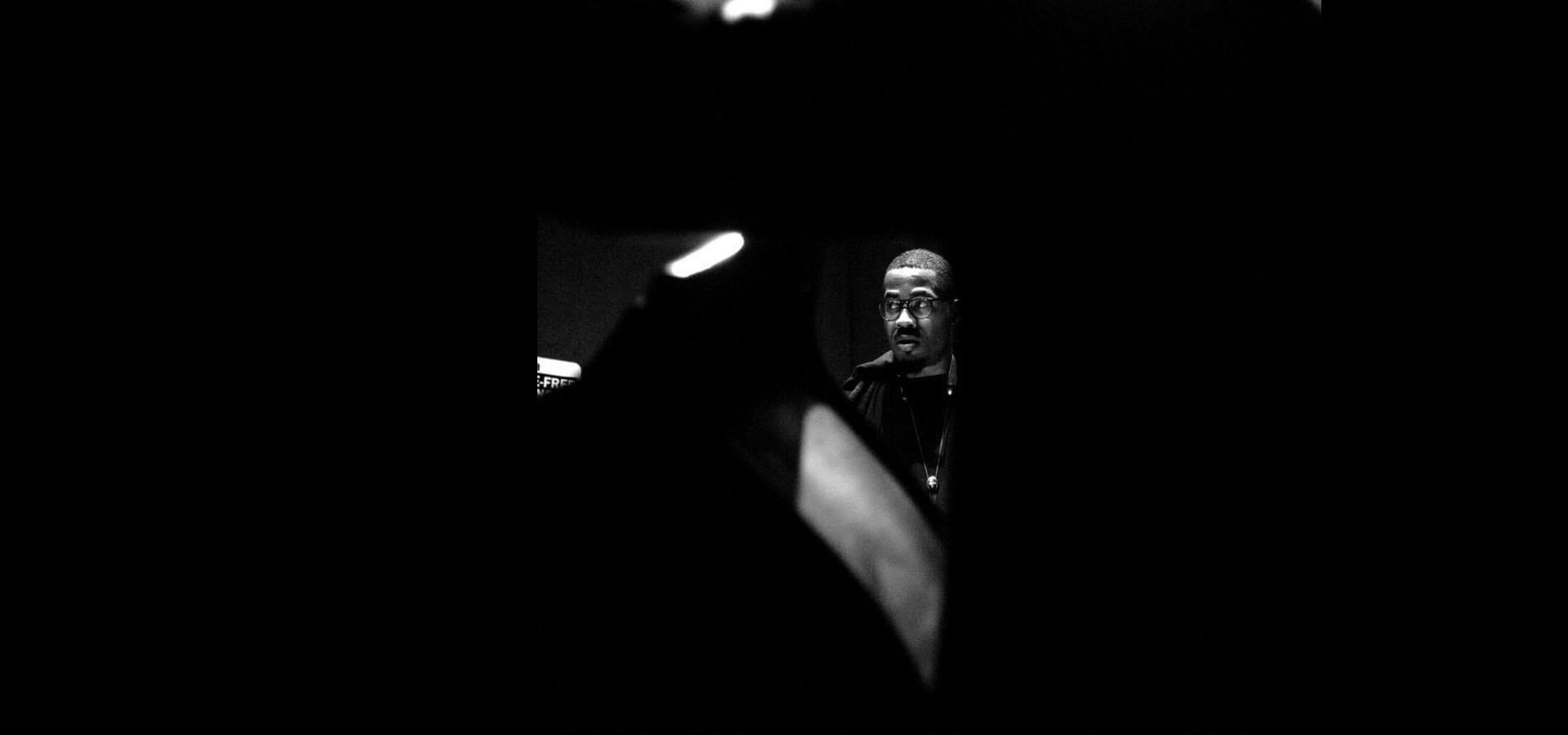

By any measure, 2020 has been a watershed year for James Brandon Lewis (Music MFA 10). In July, Lewis was named Rising Star — Tenor Saxophonist in the 2020 DownBeat Critics Poll. In the prior months, the composer and saxophone player won The ASCAP Foundation Fred Ho Award (named after the late jazz saxophonist and activist), released critically acclaimed album Live at Willisau, and was awarded a prestigious Rauschenberg Residency from the Robert Rauschenberg Foundation. While accolades are validating, Lewis, who was raised in Buffalo, N.Y. and is the son of a Baptist minister and an elementary school teacher, says he knows that the real reward comes from composing, performing with other talented musicians, recording frequently, and continuing to grow as an artist.

“To be called a rising star, voted by so many critics, is important,” says the New York-based jazz artist. “I feel like I work hard. The music reached them. But at the same time, the horn has no memory. When I pick it up, it’s on zero again. I accept it. You say thank you and keep it moving.”

Lewis, whom the Chicago Reader has called “a versatile force,” has been forging ahead since he first discovered jazz when he was in elementary school. Already interested in music thanks to the gospel singing he heard every Sunday in his dad’s church, he opted for going with his mother to summer jazz concerts at the Albright-Knox museum while other kids were playing Little League baseball. He took up the clarinet when he was 9 and switched to the sax when he was 12. Growing up in Buffalo, a hardscrabble industrial city on Lake Erie, gave him a grounding that he has never forgotten. “I would listen to Charlie Parker and say to myself, ‘There’s no way I can play like that. I have so much work to do.’ Buffalo gave me a strong work ethic to not give up. There were many hours of practicing and listening to the tradition.”

Lewis attended the Buffalo Academy for Visual and Performing Arts for eight years, beginning in fifth grade. After graduating and spending a year at Buffalo State, he transferred to Howard University where he majored in jazz studies, a program founded by trumpeter Donald Byrd. Howard’s jazz program was steeped in tradition — students had to wear ties and jackets when performing — and faculty frowned upon breaking the mold, which Lewis was eager to do. But it gave Lewis a stronger base in fundamentals and in the jazz lineage, a chance to play in many bands, and his first experience touring and performing in prestigious venues, such as The Kennedy Center.

Lewis learned about CalArts from a fellow sax player and CalArts alumnus, Kelly Corbin (Music MFA 05). “He let me know it was not a typical school,” Lewis says. “I started doing my research and felt that it would introduce me to another side of the music continuum that I didn’t know about.” Lewis applied to the master’s program in jazz and was turned down. After graduating from Howard, he lived in Denver for the next two years, performing in big bands, playing gospel music in church, and briefly attending a master’s program at the University of Denver’s Lamont School of Music. He applied to CalArts again in 2008, and this time was accepted.

Lewis studied with bassist Charlie Haden, founder of CalArts’ Jazz Program, and with trumpeter Wadada Leo Smith, a pioneer in creative contemporary music. He learned about avant-garde composers Harry Partch and John Cage. He was exposed to world music, Gamelan, and African drumming. He met animators, actors, dancers, and visual artists, among others. “My mind felt free,” he says. “I could play in ensembles with professors who had professional careers, like drummer Joe LaBarbera. I could form my own ensembles. It was open season on creativity.

“There were so many different aspects of music and art that I learned about, like conceptual thinking,” Lewis says. “CalArts opened me up to what’s possible in music. That is where I became an artist. I felt like I had a voice; that I had something to say. CalArts let me compose. There wasn’t any music that was off limits, as long as I developed a voice and was true to it and myself.”

CalArts also taught him to be a self-starter, which would come in handy throughout his professional career. The year he graduated, he recorded his first album in the Roy O. Disney Concert Hall on campus. Following graduation and a number of residencies, at the urging of his CalArts teachers, he moved to New York City so he could be in the center of the jazz world.

According to jazz critic Tony Zambito, “Lewis is usually noted for his ability to reach into the past of influences by Sonny Rollins, John Coltrane, and Ornette Coleman while crafting a unique improvisational sound that is modern and futuristic.” In New York, he organized and led many jazz groups and also co-founded a poetry and jazz ensemble called Heroes Are Gang Leaders, formed as a tribute to the late writer and activist Amiri Baraka. Over the past 10 years, Lewis has recorded eight of his own albums and five interdisciplinary albums with the poetry/jazz ensemble, which won an American Book Award for Oral Literature in 2018.

His big break came in 2014 when he was signed by Sony Records’ Okeh label, which produced two of his records and gave him the lift he needed to make a name for himself. One of the high points of his career was when Sonny Rollins asked him to perform at a Rollins tribute concert in 2017. But nothing comes easily, and Lewis says he still takes jobs to sustain his career, such as serving as the music director for an experimental marionette show at New York’s La MaMa theater in 2016.

With so many free music sites and the demise of CDs, the music industry is not what it used to be. “Now performers have to be the accountant, press person, and booking agent,” Lewis says. Asked how he manages all of these with other responsibilities and yet still has time for his music, he says, “It doesn’t take away from the music if you wake up early enough.”

While the coronavirus has temporarily shut down his touring schedule, Lewis is planning to record two new albums by the end of the year. He’s currently filling some of his free time by teaching.

“Someone once asked me how I make a living playing music,” Lewis says. “I don’t have a set answer on how to make it. I show up on time. There’s only one question on my mind. Can I pay the rent or can’t I? I’m putting my life into my music. I’m playing and playing like my life depended on it. There’s no plan B. There’s only a plan A.”