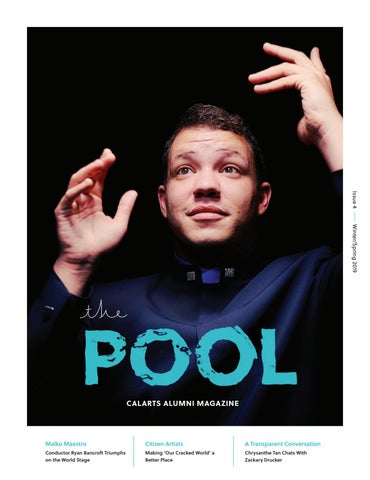

CalArts alum and It’s a Wrapper Studios founder Lyndon Barrois Sr. (Film/Video MFA 95) has come full circle. His childhood hobby of making miniature HotWheels drivers out of gum wrappers led to a successful Hollywood career in animation. Now, he’s back to meticulously shaping foil and paper to tell poignant stories.

On a cool October day, Barrois tinkers with Halloween decorations in his studio behind the Los Angeles home he shares with his wife, TV writer and showrunner Janine Sherman Barrois (Claws, Criminal Minds). He’s already set up several witches and ghouls, repurposed from old costumes, in a line on his front lawn. Some of them cackle and shriek when the wind moves them just right. Among the festive decor is a “Biden/Harris 2020” sign, the contentious and looming election arguably more daunting than any phantom specter.

Barrois is, and has always been, outspoken about political issues. His latest piece, Covid Chess Set, pits red versus blue with the pandemic as its backdrop. Frontline workers and civilians helm the blue side, while President Donald Trump and his administration lead the red. Barrois had already been planning a gum wrapper chess set at LA gallery Band of Vices for Masterpiece, a group show in which artists were asked to draw from work that influenced them. Barrois chose artists Mort Künstler and fellow CalArtian Mark Bradford (Art BFA 95, MFA 97), both of whom created art about the Civil War.

When COVID-19 was declared a pandemic in March, Barrois’ chess set evolved with the news. Press Secretary Kayleigh McEnany became a figure after she replaced Stephanie Grisham on April 7. As civil unrest brewed over George Floyd’s murder in Minneapolis, protestors holding signs were added to the blue side, squaring off against careless Florida spring breakers and men brandishing Confederate flags. Trump and Pence stand atop a pile of body bags. Dr. Deborah Birx sits in uncomfortable silence as she did when Trump talked about injecting disinfectants during a briefing on April 23. Dr. Anthony Fauci, whom Barrois calls “a hostage within the administration,” sits on the red side with his head in his hands.

For now, all 32 pieces are static in their plastic test tubes, a snapshot Barrois thinks will remain topical for months to come, no matter the result of the November presidential election. Of course, Barrois is the first to admit a structured game like chess may not be ideal for Trump, who has “written the playbook on how to get away with breaking the law as commander in chief.

“It wrecks the concept of the chessboard. It wrecks the concept of order. When your strategy is chaos, anything goes,” Barrois said.

Melvin Marshall, senior curator at Band of Vices, said he approached Barrois as a longtime admirer of his work and his take on the world. When Masterpiece opened in June, the gallery held a longer, eight-hour event to accommodate social distancing. The chess set sat in the center of the room and Marshall said guests gravitated toward it immediately.

“This is a portrait of America that represents the moment that we’re going through, but it’s still ongoing. That’s a very unusual commentary on how we’re supposed to think about this year where so much has happened, but hasn’t ended yet,” Marshall said.

Terrell Tilford, Band of Vices founder and creative director, said he’s not sure if the gallery has ever seen a piece that has spoken to its audience so strongly.

“First of all, we haven’t had a circumstance probably in all of our lives together that is quite this deep. Many of us have been in everything from New York for 9/11 through the Rodney King riots, various things over the past several decades,” he said. “But this piece really covered every demographic of what’s happening in our current events now, and I think that’s what makes it as profound as it is. Even as small and minute as they are, there’s still an emotional quality within the works. That was something that was so masterful from Lyndon; he really gave a fullness to each one of these pieces.”

Barrois often imbues his work with historical or social contexts. His CalArts thesis project in the mid-’90s, They Were the First to Ride, highlighted the Black champion jockeys of the Kentucky Derby in the late 19th and early 20th centuries. His short film “Prizefighter” focuses on boxer Jack Johnson and his fight against Jim Jeffries, the “Great White Hope” coaxed out of retirement to take the heavyweight championship back from the Black man who’d won it. Jeffries failed, but the film also highlights Jackson’s infidelity, the abuse of his wife Etta Terry Duryea, and his death. Jackson died after crashing his car when speeding away from a North Carolina diner who refused to serve him because he was Black.

“[Jackson’s life and death] is all connected to his battles with racism and the effects it had on him,” Barrois said. “He was a hero, but he was fallible. He was not a perfect individual.”

From Hotwheels to Hollywood

When Barrois was 10 years old growing up in New Orleans, his tiny figures only had one job: to pilot his HotWheels cars. The gum wrapper became his preferred medium out of convenience and scale. The figures had to be small enough to fit in the driver’s seat, and gum wrappers were plentiful due to his mother’s constant chewing. Barrois soon learned that if he sculpted his figures with the foil inward and the paper side out, he could color them and make them more lifelike.

“And because it was just so comfortable,” he said, “I never stopped making them that small.”

National attention came in 1990 after Barrois fashioned Super Bowl XXIV’s two teams—the 49ers and the Broncos—for an art show. His friend Danny Wilson emailed NBC about Barrois’ work, resulting in a segment on The TODAY Show. Soon after, Ripley’s Believe It or Not bought several figures to place in its museums.

Barrois’ next move was to apply to schools for communication and graphic design—all of which rejected him. It was only the desire to animate his wrapper sculptures that led him to apply at CalArts.

“When [CalArts] saw what I was doing, they were like, ‘Oh, my God, you have to be here.’ So I packed my bags and came down to LA. And the whole point was to come out here and make It’s a Wrapper films and do those full-time for my career.”

Barrois fondly recalls spending time in the school’s graffiti-covered SubLevel, attending annual Halloween parties, and studying with mentors such as Jules Engel, the late founder of CalArts’ experimental animation program, and Betzy Bromberg, director of the Program in Film and Video.

“[Engel offered] just constant encouragement and he was just a wealth of knowledge and experience,” Barrois said. “From Gerald McBoing-Boing to Mr. Magoo, all that stuff that I’d grown up with. It was like, ‘Whoa, I’m being taught by this guy.’”

“Between Jules and Betzy, I was home,” he added.

Though Barrois never personally felt isolated at CalArts, he did notice he was a Black student on a mostly white campus. Now, as a member of the school’s Board of Trustees, he says inclusion needs to be a key focus.

“What I’d hate to see is CalArts turn into a school for the privileged. It has a reputation as being that way because it’s not cheap,” he said. “It’s gotta be known to everyone, even underserved communities, that this is accessible for you. This is an opportunity. If you ever dreamed about working in movies or on games or on TV shows, there are places where you can go to do that, where you don’t have to feel like it’s not for you.”

Barrois has enjoyed a long career in animation, including eight years as an animation supervisor and director at visual effects studio Rhythm & Hues and nearly three years at Image Engine Design Inc. in Vancouver. His credits include visual effects for films The Matrix Reloaded, Happy Feet, Sucker Punch, The Tree of Life, and the 2011 remake of The Thing. For much of this time, his personal art took a back seat to his career.

It was while he was commuting between LA and Vancouver that he reconnected with his miniatures again. Mike Leonard, the same TODAY Show correspondent who interviewed Barrois and Wilson in 1990, pitched a follow-up segment in 2012. At the same time, Barrois’ son, Lyndon Barrois Jr., had been asking him why he wasn’t doing his own work.

“He’d say, ‘It’s great that you’re doing all these movies and stuff, but nobody on the planet does what you do. Why aren’t you doing it?’ So he sort of shamed me into it,” Barrois laughed.

Between his son’s urging and the memories the TODAY follow-up stirred, Barrois began shooting stop-motion animation on his iPhone. By 2017, Barrois was ready to make It’s a Wrapper Studios his full-time job.

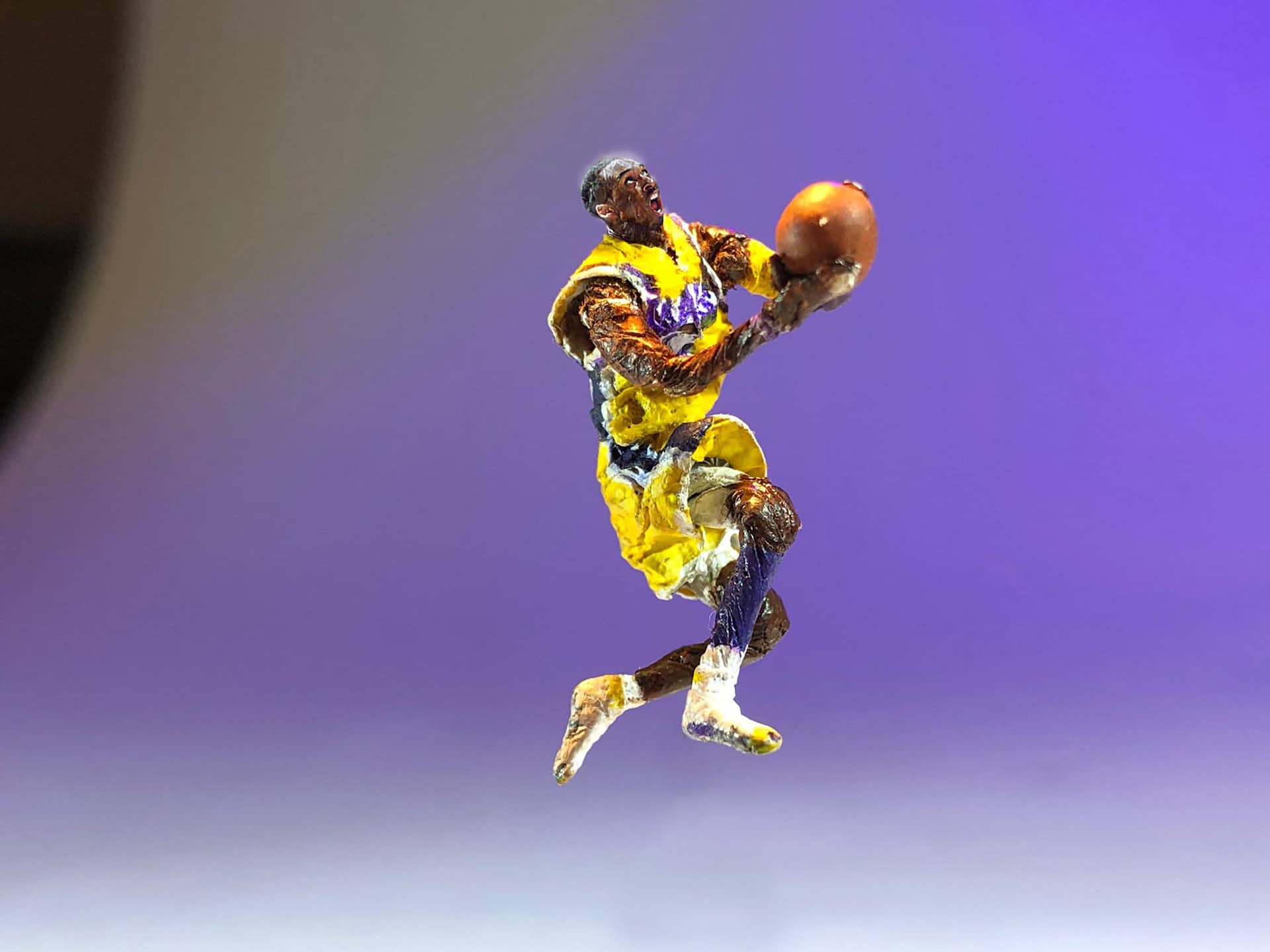

In the past three years, he’s completed numerous films and commissions, including “Monologue by Ta-nehisi Coates,” a short film on fatherhood for Topic that made the Emmy shortlist in 2019. He’s now crafting a Lakers’ piece that highlights the basketball team from the ‘70s through the early 2000s. Barrois started the piece prior to Kobe Bryant’s death this January and, in honor of Bryant, made his miniature first. In between the film and sculptures, he serves as a commissioner for the National Portrait Gallery and is a member of the Academy of Motion Picture Arts and Sciences.

And somehow, he still has time to decorate for Halloween.

View more of Barrois’ work here.