How can we collaborate creatively when we’re all locked up in our own little worlds?

When the coronavirus pandemic hit earlier this year, the world—and CalArts—pressed the “pause” button. Students dispersed across time zones as campus cleared out. No one knew with any certainty when they might return. The faculty took a moment to regroup and rethink teaching in a stay-at-home world. But, in a matter of days, a new pedagogy evolved.

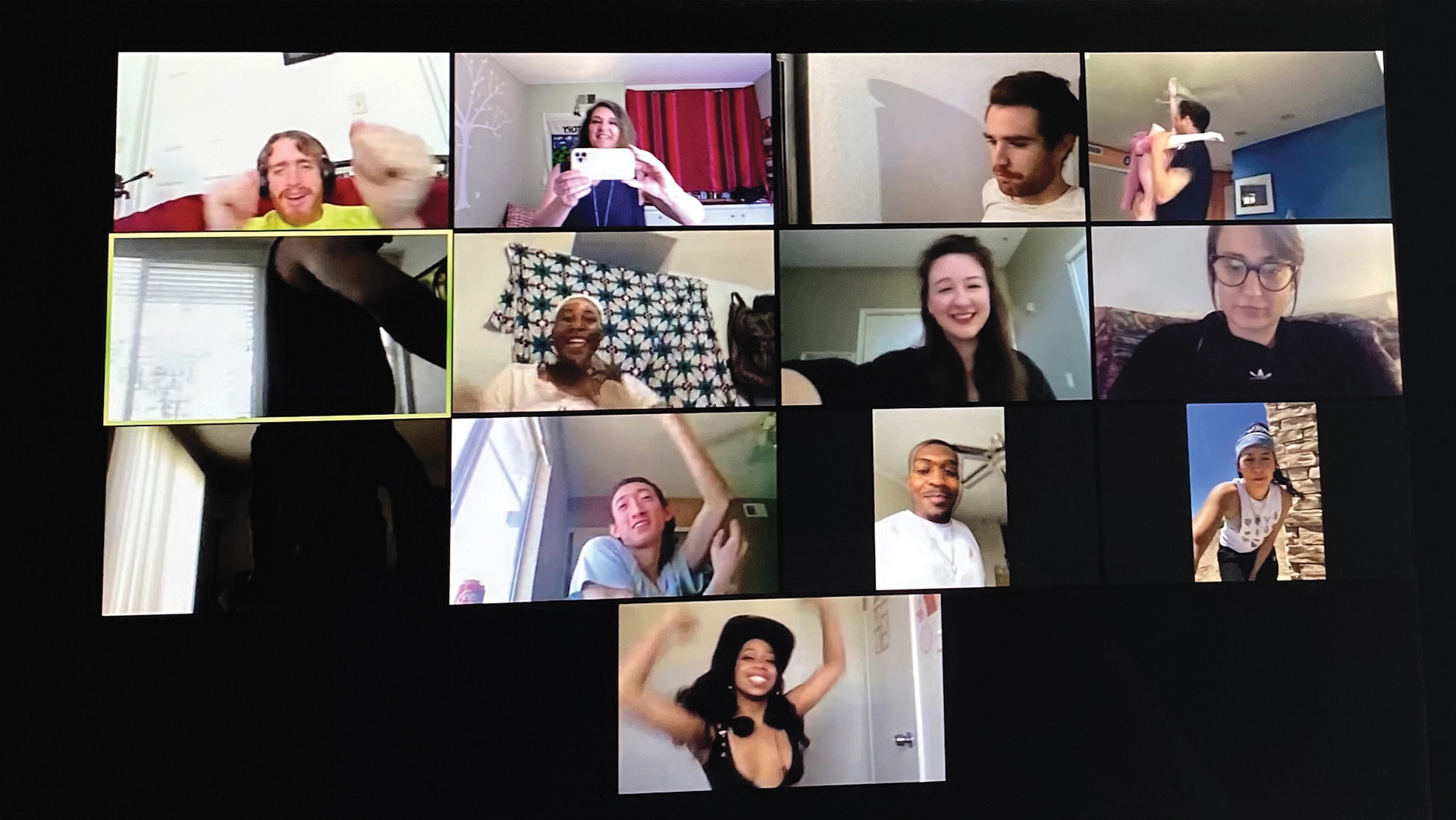

At first, letting CalArtians learn on their own time felt like a natural accommodation. Faculty posted course materials online, establishing asynchronous classes, which don’t meet at any particular time, to give everyone extra flexibility. Then it happened: Students gravitated back toward the classroom experience—as close as they could get, anyway. They wanted to assemble. They wanted to hear and see one another in real time. Before long, they were figuring out time differences and logistics to keep the CalArts community connected.

In the weeks since, virtual learning spaces have bloomed across CalArts. Faculty members scrambled to experiment and reimagine coursework for the remote-learning reality. Unsatisfied with basic video conferencing, they’re refashioning online education for unprecedented times—and with breakneck speed.

Their results aren’t just keeping CalArtians engaged. They’ve also stoked fresh thinking, new creativity, and a renewed sense of togetherness and hope. “I’m glad to be at CalArts with this faculty and these students,” said CalArts President Ravi Rajan. “Together, we will be the ones to create something truly unique in this moment—a model for arts pedagogy moving forward.”

Here are just a few examples.

The computer screen as canvas

Film/Video

The computer screen as canvas

In a normal semester, artists in Rebecca Baron’s The Essay Film course would include live cinema performances during class. They would use equipment from the Film Cage. They would enjoy the easy back-and-forth of their classmates’ ideas and reactions.

This spring has brought them a different lesson: improvisation. Working from home, some students are tethering their smartphones and laptops to make recording projects possible. Troubleshooting has become a regular part of class, a sort of mutual support for technical challenges.

Many students are using technology to keep in better and more meaningful contact with one another, said Baron, a filmmaker and faculty member in the School of Film/Video. She sees them recognizing the importance of the community and togetherness, she said.

One example: Attendance in her virtual sessions has been perfect.

“My class has had this incredible conversation that’s been developing over weeks,” Baron said. “It’s been hard to do without the in-person contact, but I’ve been moved by the quality of conversation, the level of critique that we have been able to achieve in these circumstances. People are really reaching toward each other, making the best of the situation.”

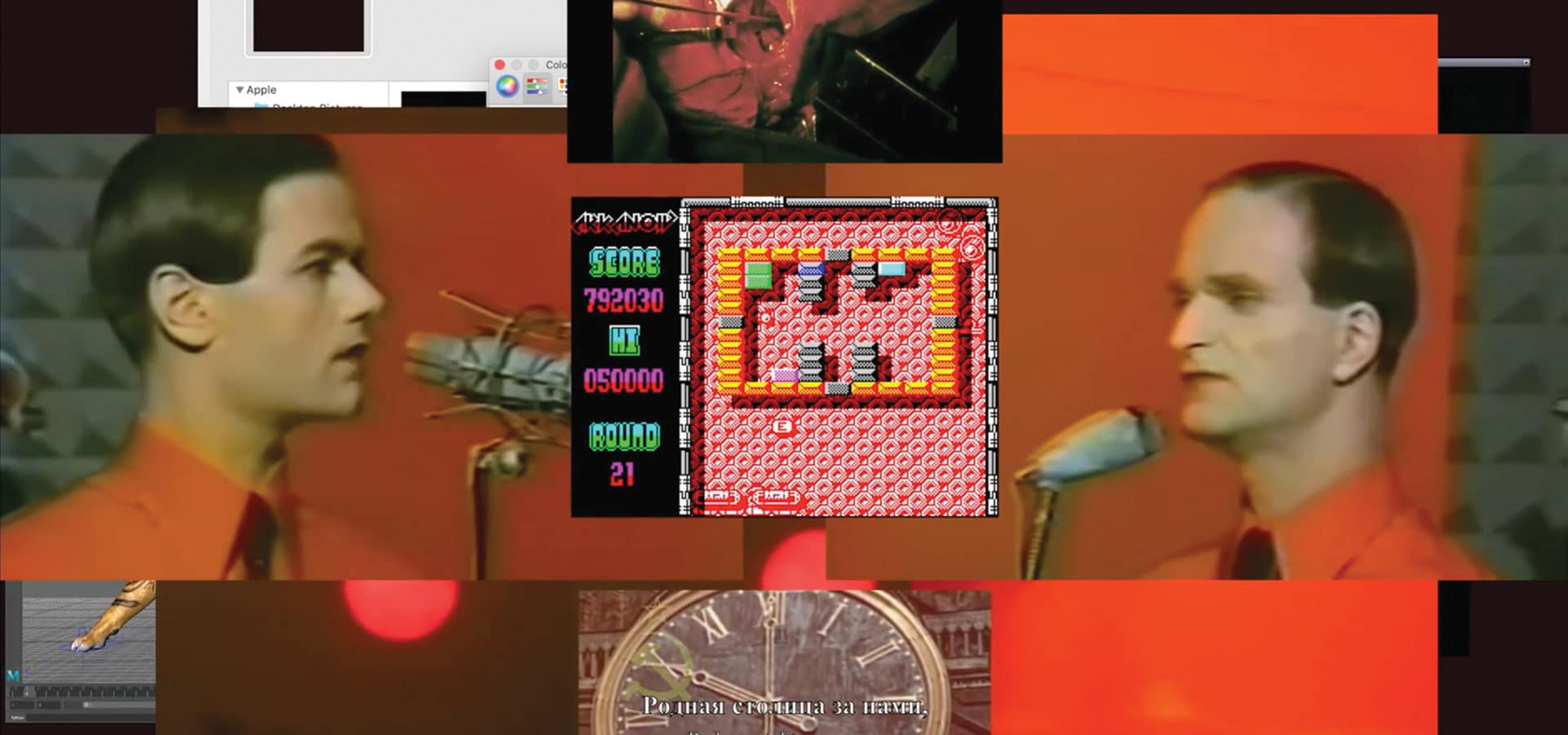

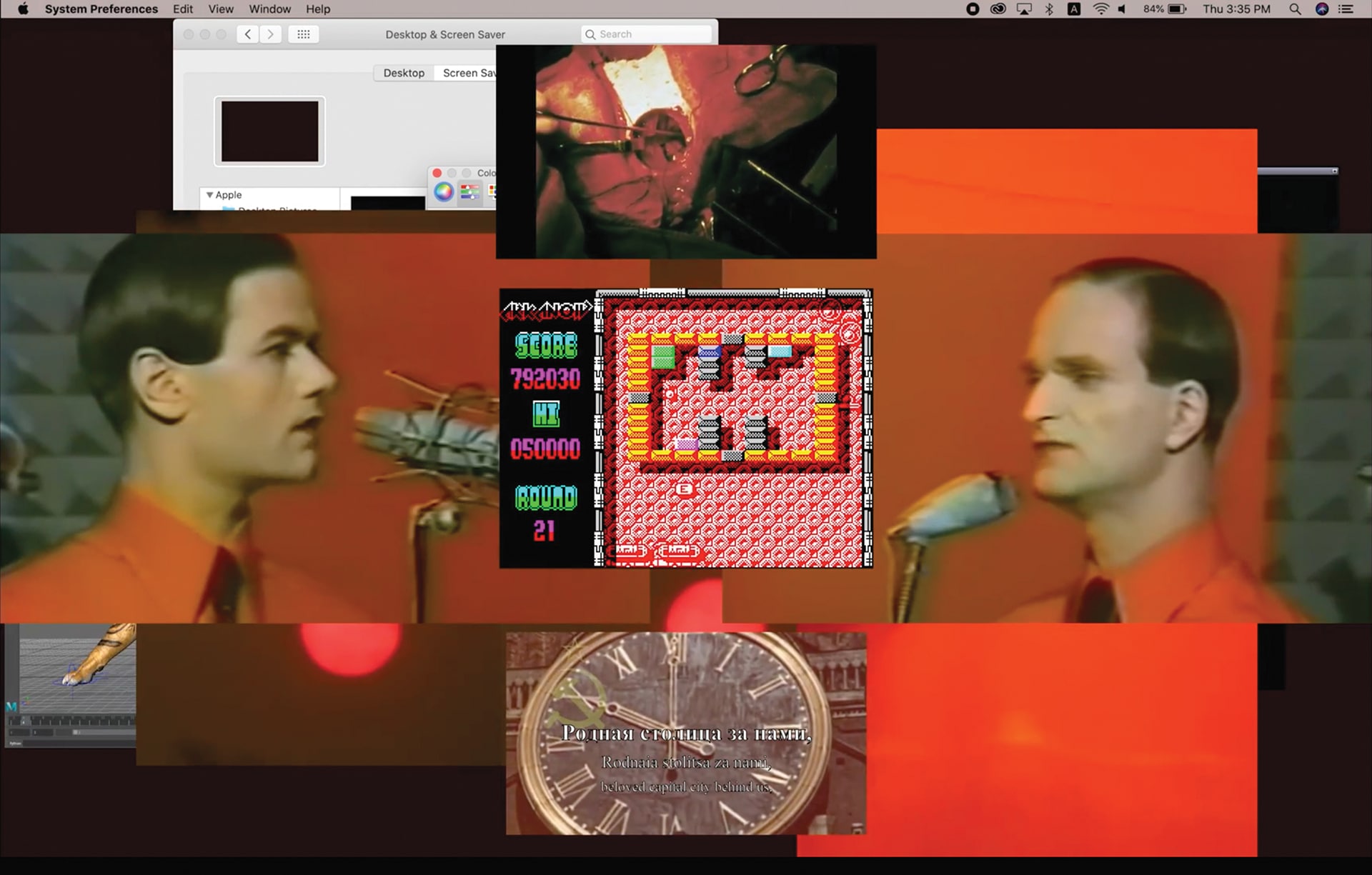

By strange coincidence, when remote instruction started, Baron had already planned to spend several weeks on desktop filmmaking, which features the computer screen as the canvas. Artists record the screen itself and choreograph actions on the desktop, guiding the viewer through opening windows, browsing, producing text, tiling, and layering images to tell a story or create abstract montages. At a time when the computer is particularly central to daily life, Baron said, “we’re opening up other possibilities of the screen.”

The candle, the myth, the legend. Mountain Lodge, by Jordan Wong.

Baron has worked across platforms such as the messaging service Slack and the conferencing service Zoom to help students observe and discuss one another’s work in real time. At times, the class pauses while everyone separately watches a prerecorded video, then resumes via Zoom for discussion.

As some students have adapted their prior work to the new conditions, others are “stopping what they had been doing and trying to respond to the circumstances” with new projects, Baron said. “It’s a very individual thing.”

I’ll Be Your Catoptric Cistula, by Alex Broadwell.

Her own circumstances have allowed her husband, Scripps College faculty member Douglas Goodwin, to make impromptu Zoom appearances before her students. “It’s kind of family-style teaching right now,” Baron said. “We’re all getting to know one another’s pets.”

Deploying digital platforms for science

Critical Studies

Mike Bryant brings a touch of the theatrical to his science courses. His rendering of DNA extraction in his class Introduction to Science at Method isn’t to be missed. He gargles and spits out Gatorade and then proceeds to demonstrate a MacGyver-style extraction with the use of household items, including shampoo, salt, rubbing alcohol, and meat tenderizer. But he isn’t relying on office-style video conferencing to give his students that visual. He’s employing TikTok, the popular micro-video service that lets users record and post 15-second (and longer) clips. His inspiration came from students last semester who introduced him to the platform.

“I thought: ‘If I’m going online and recording all these lectures, why not do them as TikToks, too?’ There are some TikTok trends that you can use to drive the story, in part by showing differences among key concepts,” said Bryant, a biologist and associate dean in the School of Critical Studies.

His take: Using a device like TikTok or a meme can capture the fundamental core of a big idea—and force him, as the teacher, to contemplate what he’s inadvertently left out. “The format means I have to boil these things down to their most essential attributes,” Bryant said. “These are really scary times. So something that’s a little bit funny or entertaining or quirky—that does help students engage. If it’s done properly, it can be funny; it just can’t be only a joke.”

In his class Biology of Politics, a final assignment centers on making a prediction about a future society. Students have a choice: They can write a term paper or try something more creative to “convince me that they learned something,” Bryant said.

Those creative possibilities might include a song, a monologue, a graphic rendering, or several TikToks. “It’s not just like, ‘There’s four TikToks; thanks for the semester,’” Bryant explained. “It’s four TikToks, and ‘Here’s the theory behind it and why.’”

That spirit of flexibility is crucial in these times, he said. He has adjusted due dates, reworked class logistics, and learned the nuances of remote learning, such as the blank boxes that appear on screen when students switch off their cameras. “It’s new for all of us,” Bryant said. “I’m just trying to make things as flexible as possible.”

Seeing this moment through literary characters

Theater

As pandemic-related closures were instituted in Southern California, the MFA 1 Acting Studio class had been exploring William Congreve’s 18th-century play The Way of the World. School of Theater faculty member Marissa Chibas saw an opening: Actors in the class could create 60-second pieces as their Way of the World characters’ responses to the 21st-century crisis. “I was trying to find a way to honor the work we were doing while acknowledging the incredible moment we’re in now, not ignore it,” Chibas said.

In mid-April, the students made their first-draft videos. For many, it was the first time they had crafted their own content like that. Some did it in complete isolation.

“They’re holding up pretty well. I think there are moments of being overwhelmed,” she said. “It’s important that, as the mentor, I say: ‘If you have to take a break, you can take a break.’ This is huge what we are going through together.”

Chibas’ other Acting Studio class with BFA 3 students centers on theater material that she chooses. For these students, the pandemic marks “a way to delve into their characters, and maybe find some new terrain for character portrayals,” she said. “For many students, this type of work is a way of processing, a way of expressing and maybe finding another outlet” for deep-seated reactions to the crisis.

Remote learning has helped acting students cultivate other skills, including self-taping and establishing a level of comfort in front of the camera. Chibas is planning a storytelling opportunity for her students that’s similar in style to The Moth Radio Hour.

“It’s a great skill for actors to tell a good story in a short period of time about themselves, their lives,” she said. “We wouldn’t be doing this had it not been for the pandemic. I can only imagine being so young and new to the world in many ways—what this might be like for them.”

The ability to tell stories has found renewed appreciation amid the pandemic, and acting students feel that, Chibas said. She’s seeing “a tremendous amount of support and kindness through this,” including in exchanges among students. “None of us can go on as usual. We have to face this moment and work together creatively to respond to this moment,” she said. “I think from now on, that’s going to be very alive in [our students]—the importance of the artist’s response to a particular time.”

The following videos were created by CalArts Students during the 2020 pandemic. The actors imagine their characters` response during this historic event.

Pivoting to podcast

Art

Louise Sandhaus (Art MFA 94) was a CalArts student herself when the Northridge earthquake struck Los Angeles County in 1994 and closed the CalArts campus. She remembers feeling unmoored and uncertain about whether and how classes would continue.

So when the coronavirus upended routines for students, it was especially important to her that she hold the Symposium Workshop class during the week classes were paused, even if “it was virtually and just to connect.”

“These students have shown so much resourcefulness and agility,” said Sandhaus, a faculty member in the Graphic Design Program within the School of Art. “I think that resourcefulness is a form of creativity.”

Participants in the class, which operates like a collective, choose a subject each year that demands a larger conversation, leading to a public event. For this year’s scheduled event at REDCAT in April, a panel of Graphic Design alumnae were set to discuss practices that have given them a sense of agency and growth. The plan ran into trouble when the event fell victim to COVID-19-related cancellations.

Undeterred, students in the collective pivoted to reshape the effort as a podcast series.

“It didn’t feel like a compromise. It felt like maybe this was the better opportunity,” said Sandhaus, who advises and mentors the group.

A half-dozen interviews were in the works as of mid-April. Each episode will be 20–30 minutes, featuring people who would have been panelists at the canceled event. The students have named the podcast Radical Practice, focusing on “alternative modes of success and how our alumnx peers from the Graphic Design Program define themselves in their work,” said student Natalie Gooden (Art BFA 22).

She and her co-collaborators have learned podcast technology on the fly. They’re fast acquiring new skills, a reflection of the growth and creativity fostered in times of trouble, Gooden said. Plus, using a podcast as their medium means the work will have staying power and broader reach, student Shu Chin Yeh added. “We all have this collective drive to make it happen,” Gooden said.

When this generation of artists emerges from hardships of the pandemic, Sandhaus suspects they will formulate new ways of working—including new design practices. “I think adversity can lead to all kinds of new ways of doing things, new kinds of visual language, and new ways of addressing the moment,” she said. “I hope that’s what will happen now.”

Across the miles, making music

Music

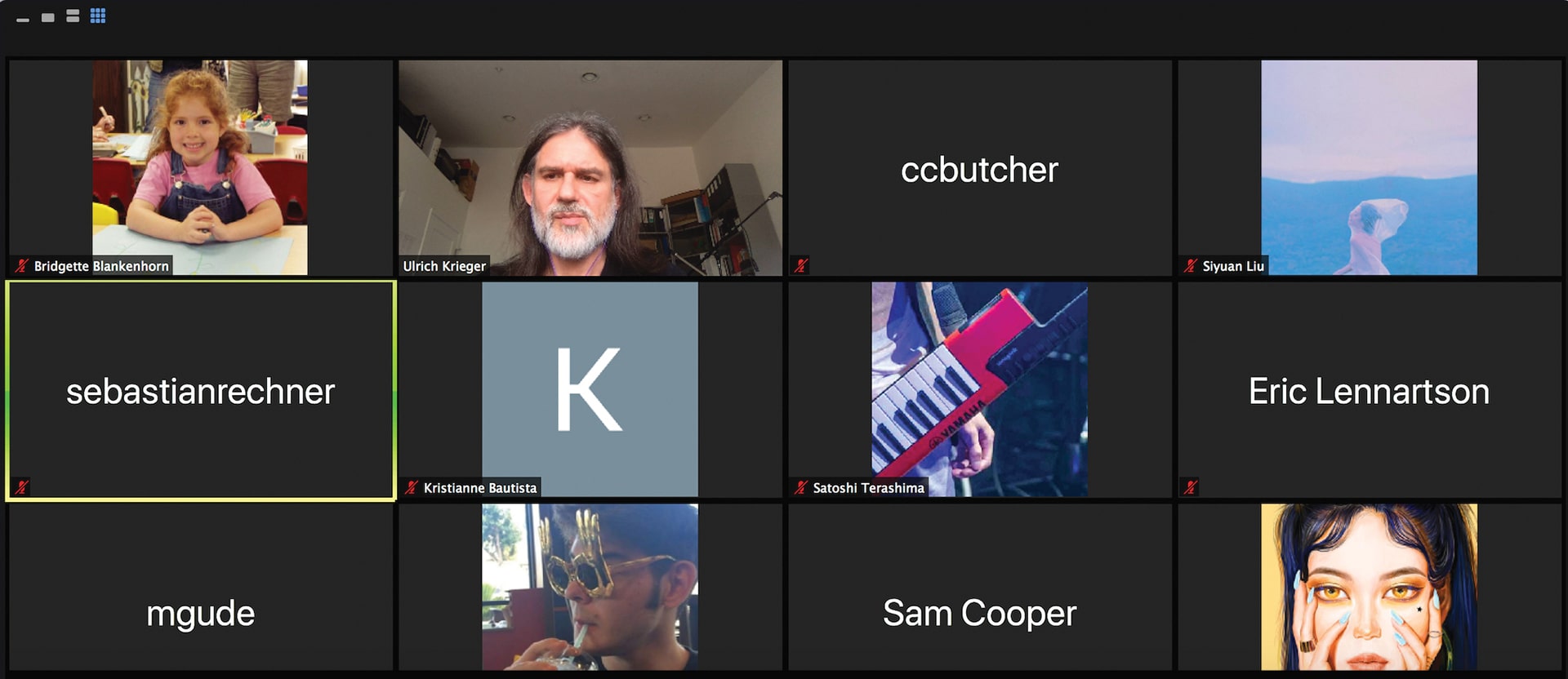

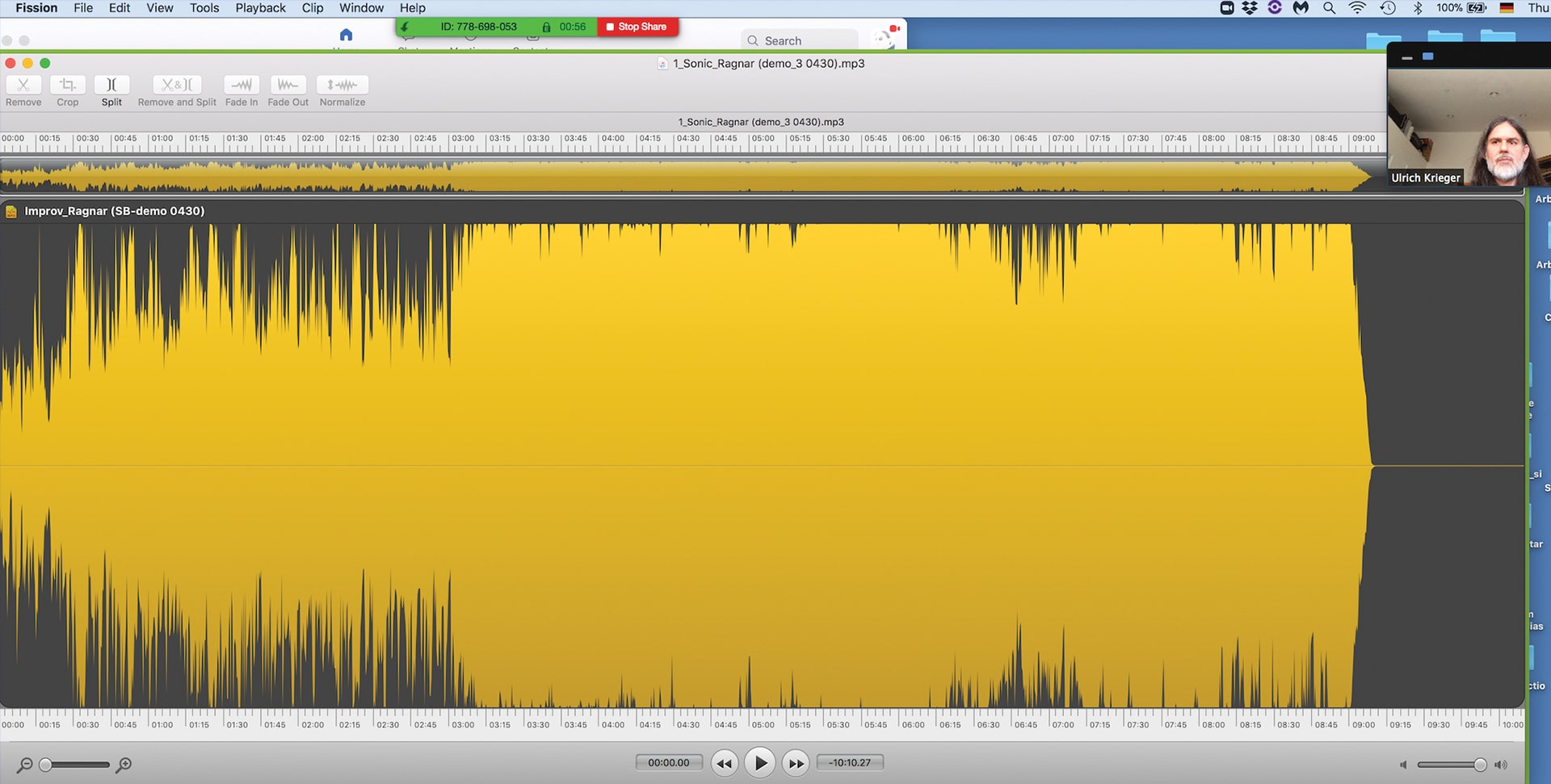

For a typical conversation, part of Zoom’s convenience rests in its restrictions: Only one person at a time can be heard. The idea is to keep people from talking over one another. But that’s exactly what makes the popular platform so difficult for musicians who want to explore live music and jam together. In fact, there’s little technology available that enables that style of online collaboration, said Ulrich Krieger, a faculty member in Composition and Experimental Sound Practices in The Herb Alpert School of Music at CalArts.

Part of the issue is latency, or that time delay between when one party speaks and another party hears it. “It makes it nearly impossible for a group to play together online,” said Krieger, who is also a composer and experimental rock musician. That made for significant complications for his Sonic Boom class, where musicians develop music and play together.

Krieger’s solution relies on ingenuity and his own experience. He started by having students make separate, 10-minute recordings of a piece known as “und der Rhein gibt sein Gold nicht preis,” an ambient music deconstruction of Richard Wagner’s 1869 overture to the opera Das Rheingold. Students only needed the score and a stopwatch.

Composed and mixed by Ulrich Krieger, performed remotely by Sonci Boom, CalArts. This piece is an experimental ambient de-re-construction of Richard Wagner’s Rheingold Overture.

Krieger superimposed those recordings to create a collective production. “We’re all surprised how good it sounded, with people just recording individually, following a stopwatch and a score,” he said.

Then came “Avoid the Funk,” a rock production that started with a drum track uploaded by Krieger. Students developed it from there using a snowball effect, each of them downloading the sound file, adding a new layer to the recording—vocals, for instance—and passing it along to the next person. The general philosophy already has legs in the commercial music world, Krieger said. But for a music class, “starting something like this from scratch online is a real experiment.”

“I think [all-remote learning] might change academia and learning overall,” Krieger said, forecasting a future richer with online instruction and collaboration. The pandemic crisis “definitely changes what it means to be a musician.”

While technology will evolve to ease digital hurdles like latency, he said, people won’t give up the in-person experience. “As much as we’ve had recordings through the 20th century, people want to go to shows. They want to see live musicians. All these livestreams online—they’re nice, but they don’t really replace a concert where you sit in a room with people,” Krieger said.

In the meantime, he said, artists are using the cabin fever that’s become a secondary scourge of the pandemic: The extra time on their hands has unleashed a wave of new creativity.

“The more people have something they can do for themselves, the less they get bored,” Krieger said.

Concept and mixing by Ulrich Krieger, performed remotely by Sonic Boom, CalArts.

Dance

A return to Hip Hop’s origins

On their driveways and in the streets, Nina Flagg’s dance students are taking Hip Hop back to its roots. They’re used to a sprung floor and indoor comforts in the studio spaces of The Sharon Disney Lund School of Dance, but those amenities were controversial when the genre first shifted from the streets to studios, Flagg said. “People felt like the essence of Hip Hop culture would be lost—being in the club until 7 or 8 a.m., the sound, the energy,” she said. “That was a huge thing.”

Now that students in her Hip Hop Composition and Hip Hop Technique courses are taking their dance sessions home, “there’s almost this return to the original practice, where you have to cultivate your skills before you go back out into the community, whether that’s to battle or just to share,” Flagg said.

Moving the classes away from conventional studios has led her to redefine and repurpose the very idea of a studio, she said. With some students dancing on concrete and others on carpet, Flagg has focused more on concepts of buoyancy and relationships with the floor. For the time being, she has given up sneakers to lead her classes barefoot instead. That works best on her living room carpet, Flagg said. “Of course, these adjustments change the way you move and your relationship to technique,” she said. “I had to take a moment myself to adjust, to be able to present to students in a way that maintained our standards.”

After trying asynchronous online sessions, she has switched to teaching in real time via Zoom. In a way, all the changes mirror Hip Hop’s natural emphasis on evolution and social movements, Flagg said. “Now we are socializing through digital platforms. We miss some of the elements that really shape how you participate in Hip Hop culture,” she said. “At the same time, this is a testament to Hip Hop culture—taking your resources and repurposing them to make something greater than their original intention.”

She sees elevated creativity, thinking, and attention to detail in her students’ work these days. They’ve become their own stage managers, lighting designers, editors, and directors.

“I’m hoping this broadens their vision of what is art-making,” Flagg said. “Because of comfort, repetition, and regimen, we tend to have a myopic view of creation. I think that this time—hopefully—has opened up everybody’s view and perspective and stretched the peripheral vision of art-making. We don’t want students to slip back into a comfortable way of thinking about art.”

Technique class.