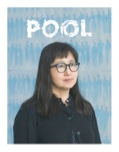

Amanda Yates Garcia talks witchcraft with Ravi Rajan

“I wear all sorts of spiritual hats, only some of which are tall and pointy,” says self-proclaimed witch, Amanda Yates Garcia (Critical Studies and Film/Video 06). She writes, performs, leads workshops, and conducts private sessions with clients, coaching them on life’s most pressing personal and professional challenges. Her toolbox for doing so includes an especially wide array of esoteric strategies including the “Western mystery traditions of tarot, alchemy, and Hermeticism; shamanic healing practices of the Northern European tradition; positive magic and witchcraft; herbalism; energy work; and psychomagic.”

CalArts President Ravi Rajan recently invited Yates Garcia to return to campus. Her visit included a sit-down with Ravi in which they discussed a range of subjects at the intersections of art, philosophy, and her time spent at the Institute.

Ravi Rajan: Thank you for coming.

Amanda Yates Garcia: Thanks for having me. It’s a pleasure to be here.

RR: In the first two years that I’ve been here I’ve had the luxury of meeting so many different CalArtians, and it’s been one of the most fun parts of the job. What I’ve found is that every one of them has a different story of how they ended up at CalArts. What’s yours?

“I wear all sorts of spiritual hats, only some of which are tall and pointy”

“There are no spectators. There are no witnesses. Everybody is a participant. Everybody is a priest or priestess.”

AYG: I was living in London and had done my undergrad in dance at the Laban Center for Movement and Dance. I became frustrated working so hard on the choreography of my pieces, and seeing that once they were performed, they were gone. I wanted to create something more lasting, and began making dance films. I was also writing. I had written a novel that I was trying to get published, but felt I needed time to go more deeply into both dance and writing, and to think about them in a space in which I could apply rigor—and also have time to steep as an artist. I wasn’t sure what to do or where to go. Because I have a spiritual practice, I had asked the Goddess where I needed to go next and what I needed to do. I took a walk on the south bank in London and went into the National Film Institute where I watched a film and picked up a piece of promotional literature from CalArts. In it I saw that there was both a film program and a writing program here, and I felt like, that’s it. I applied to both programs, was accepted by both, and the rest is history.

RR: Excellent. So, there are many threads to unpack here. Maybe we can go into a couple. Why did you choose London? And how did you end up in dance?

AYG: When I was in my late teens, I attended the community college where I grew up, in Santa Barbara. I’m a seventh generation Californian. In my late teens I was going through a really difficult time, spiritually, emotionally, psychologically—a lot of my new book is about that period. I was studying philosophy and art history, but also taking dance classes as a way to pull myself back into my body and find some grounding. And I just loved it.

RR: You didn’t dance when you were younger than college age?

AYG: No, not really. I found dance at City College. There was something about dancing—it was the only time I was happy. I just loved to move and loved that direct expression. I was also writing—I’ve written since I was a child, but at that point was feeling that dance was something I needed to pursue. Through a series of mishaps, I ended up moving to San Francisco, then Amsterdam for a year, followed by six in London. So I lived abroad all of my early adult life. When I got back, I came to CalArts, which was really exciting.

RR: How long were you here?

AYG: I was here for three years because I was an InterSchool student in writing and Film/Video. But I made a lot of really angry work while I was here.

RR: Would you characterize yourself as angry at that time? Or is that just what came out?

AYG: I think I really was angry. I had had a lot of trauma in my life, and had come from a family legacy of that, and I also looked at the world around me and saw all the trouble in the world. I was angry about that, too. I completed my three years here and shortly after graduating I had an epiphany. I had the realization that it’s easy to point out all the things we don’t like about the world; easy to point out everything we think is wrong; but it takes a lot more courage and gumption, and, I think, intelligence, to ask, what should we do instead? To stake a claim, to make a stand—even if you’re wrong—but to at least try and make a more just and beautiful world. That’s what I wanted to do.

“I wanted to live in a world where witches exist; where women are powerful; where we see nature as sacred, enchanted and beautiful.”

RR: I got goose bumps when you said that. It’s such an important thing. That realization, that artists must move from research to action, is important. So much of school is focused on creating critical thinking and developing the ability to analyze and deconstruct something. But artists are important in creating the next “thing,” right? Creating a new model. And if you don’t make that jump, it’s a tough moment.

AYG: Yes, there was just some kind of dawning awareness as I exited my Saturn Return at the end of my 20s. I was brought up practicing witchcraft. I was brought up by a witch, and so I think that history influenced my practice as well.

RR: That was the other thread, witchcraft.

AYG: In my late teens, when I was having all that turmoil, I had really turned away from witchcraft in the way that many people turn away from the religions they were brought up with—you know, rejecting that. Thinking, “That’s my parents’ thing, and I’m not into that.”

RR: Growing up in Oklahoma I knew folks who had lots of different experiences with organized religion or spirituality across the whole gamut … from a casual relationship to it, to a fundamentalist one, to super serious—like dedicating their whole lives to it. So, describe a little bit of that time to give us some context.

AYG: Witchcraft is an anarchistic spiritual practice; my mother calls it “Earth-centered Spirituality.” Essentially, there’s no top-down organizing body that tells you what to do; it’s from the ground up, which means that my mother had a coven that met every month on the full moon, and they chanted and did rituals related to nature. Witchcraft is a nature religion, very much about personal empowerment. There are no spectators; there are no witnesses. Everybody is a participant. Everybody is a priest or priestess.

RR: So it’s an individual practice but there is a group, almost like a co-op or a commons, where you would get together?

AYG: There are many solo practitioners but there’s not a “pope”; no final authority. There’s not a singular text. There’s no bible; it’s a mystical tradition, so it’s about direct relationship with the divine and, essentially, witches see the divine as imminent in nature. It’s coming through in material reality and we’re part of that. It’s not something transcendent that we’re trying to contact as outside of us but something that also comes forth from within us, us inside the more-than-human world. The planet is alive and inspirited. There’s a complex theology around it.

RR: There are many theological explanations, right? I mean every religion finds one way or another to deal with that. If you think about Christianity, every flavor is slightly different and might be more or less in tune with that. Growing up in a Hindu household, within the spectrum of Hinduism, there were stronger and weaker relationships to that understanding that the universal is here, it’s present. …

AYG: Yes.

RR: It’s interesting to hear about witchcraft as a practice. So for you there was that moment that we all have, I guess in our teens: it’s about a change in practice … you want to do something else.

AYG: Yes, in my late teens I really made art my religion; I was devoted to it. I was a devotee kneeling at the altar of dance, as well as with writing, with film, with art in general. In London I used to go into the museums as if they were sacred temples.

RR: They are.

AYG: I saw that one of the things that I was rejecting about the world and one of the things that I was angry about was the disenchanted nature of white supremacist, capitalist culture, patriarchal culture, because within it everything is available for exploitation and nothing is sacred. But I felt that the arts had become this repository of the sacred and the enchanted, and, in fact, one of the only places in our culture where that was allowed to exist. When I left CalArts, my artistic crisis came about because I didn’t just want my work to be about pointing out how horrible white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy is, but instead wanted to create the world that I wanted to live in, to create something else; to find a way outside it somehow.

RR: And how did you describe that?

AYG: I wanted to live in a world where witches exist; where women are powerful; where we see nature as sacred, enchanted, and beautiful. Alive and numinous, with spirit. I decided that I was going to create that world with what I had available to me, right beneath me on the ground. I returned to witchcraft because that was what I knew. I started to do ritual performances, and people started asking me to do them privately, and I created a business doing it as an artist.

So, the work I’m doing now is a return to sacred art forms, including those of antiquity, but very much from a contemporary, modern perspective. Much of my practice develops from the desire to find a way to live in the world without sacrificing the things I hold most dear. After I finished CalArts, when I was working in museum education and adjunct teaching, I hated it. It was so stressful. You don’t make any money; you’re working so hard, and I just felt exploited. You’re scrambling, trying to maintain your artistic practice. And the artists that I knew who were working within the gallery system treated it like a business.

RR: It’s the industry of art.

AYG: Exactly.

RR: Many like to call it an “art world” but it’s an industry—just like the film industry, the music industry.

AYG: As an act of resistance, I decided I was going to find a way to do the work that I wanted to do and make the work I wanted to make, which required creating a framework that would include supporting and sustaining myself.

RR: How long before this shift of consciousness happened?

AYG: There are no overnight successes. People are usually working hard over a long period of time. I had to do that. It took me five or six years. And then I started leading monthly workshops called “Magical Praxis” in which I was integrating magic, critical theory, and art in one monthly event. Lots of artists came to those. One of the great things about CalArts is the community that develops, and the connections one makes here. It’s one of the things people don’t tell you about the values of grad school.

“They wanted Tucker Carlson to interview me. I said no several times, but Fox kept calling me back. People in my life said, ‘Do not do this. It’s going to be really bad for you.’”

RR: Especially CalArts.

AYG: Many years ago, through contacts I’d made here, a writer from the LA Times attended one of my events, and wrote in the Times about a ritual I’d done at Magical Praxis to bind Donald Trump from causing harm. That ritual was started by the ceremonial magician Michael M. Hughes, and then many other witches, including myself took up the cause. Because witchcraft is an act of resistance, it’s always been very political in nature. About nine months after the story came out in the Times, I was contacted by Fox News. They wanted Tucker Carlson to interview me. He’s a conservative and there was no way I was going to do that. I was scared—literally scared for my life. But the spirit guides I work with, one might call them “your intuition,” they kept telling me, “You need to do this.”

I said no several times, but Fox kept calling me back. People in my life said, “Do not do this. It’s going to be really bad for you. You’re going to get humiliated; he’s going to make fun of you; people are going to threaten to kill you.” All except one fellow CalArtian, Margaret Wappler [Critical Studies MFA ’04], who I went to grad school with, and an honorary CalArtian, Jade Chang, another writer, who said, “You can take this guy.” I was like uh … maybe. But when my guides woke me up in the middle of the night about it, I got up and e-mailed Fox and told them I’d go on. I had watched some interviews that Carlson had done in which he yelled at and humiliated the folks who were on his show. I saw that he really went for blood if they started to get angry. I told myself, “Nothing he says is going to make me angry. He’s not going to knock me off the pillar of love, no matter what he does.” I went on and was able to keep my cool, and then it was insane. As I was leaving, I felt like I was getting washed in waves of intensity; J. K. Rowling retweeted the segment and it went viral. An agent from New York contacted me and asked if I’d ever thought of writing a book. I’d actually been working on a book proposal for the past six months and was just about to send it out.

RR: So the agent found you at just the right time. The Tucker Carlson interview is also how I discovered your work.

AYG: That’s so funny. Who knew that he would make my career?

RR: That’s a fantastic story. It seems like CalArts helped you bring these threads together in some way, right?

AYG: Yes, I’m still super tight with my CalArts people. It was the connections I made at CalArts that led to the LA Times writer being at my Magical Praxis event, which ultimately led to getting my book, Initiated: Memoir of a Witch, being published this October by Grand Central/Hachette.

On September 17, Alumna Amanda Yates Garcia was interviewed on campus by CalArts President Ravi Rajan. In the piece of their conversation excerpted here, Yates Garcia shares details of her personal struggle to find her singular voice as an artist, and to create work true to herself–her beliefs, values and experience.