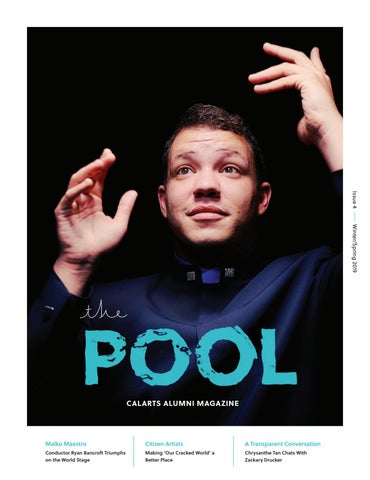

David Rosenboom steps down as dean of The Herb Alpert School of Music at CalArts after 30 years. The Pool pays tribute to Rosenboom’s multidimensional career as both an acclaimed performer-composer and innovative educator with two stories penned by Julian Cowley and Mark Swed, two prominent music journalists.

Overseeing and directing a school of 300 students, three programs, and twelve specializations are challenging to say the least. Rosenboom is the first to suggest that he “couldn’t have done it alone.” His faculty, students, and administrative colleagues were all instrumental participants in his orchestrated efforts. That said, under Rosenboom’s leadership The School of Music was transformed in many fundamental ways: some of them quantitative, all of them qualitative. Its student population tripled in size; gender diversity among faculty increased significantly; program specializations now include Performer-Composer, Music Technology, Musical Arts/ Experimental Pop, and Composition and Experimental Sound Practices; development of the first doctoral program at CalArts (DMA Performer- Composer); establishment of academic international exchange programs; and vigorous support for career development initiatives.

New facilities created on Rosenboom’s watch include the Wild Beast Concert Pavilion and S. Mark Taper Foundation Courtyard, the Wave Cave, the Machine Lab, and the Dizzy Gillespie Digital and Roy O. Disney Recital Hall recording studios. He created innovative programming for REDCAT and performed many times at the downtown venue; established a concert series at REDCAT and the Wild Beast Concert Series on campus; and partnered with prominent cultural institutions throughout Greater Los Angeles, including the Skirball Cultural Center, MOCA, LACMA, The Music Center, and the Getty Center.

And through it all, Rosenboom managed to travel and perform internationally, create fourteen albums of his own music, and to raise a family.

PART I

In the Laboratory of Music

BY JULIAN COWLEY

David Rosenboom sums up the qualities that have kept him at the forefront of adventurous music-making for more than half a century: “I’m an explorer and an investigator.” Rosenboom embodies an experimental outlook, a need to unsettle common assumptions, and take the measure of new possibilities. Luminaries such as Charles Ives, Henry Cowell, Harry Partch, or John Cage might be cited as precursors, not in terms of specific musical values, rather Rosenboom shares their restless and fertile imagination. Conceptually lucid and technically resourceful, his music is testimony to robust independence of mind. “Composition students used to be taught to find an identifiable individual voice and stick with it,” he says. “I was never able to develop an interest in crafting a musical style. I give myself the freedom to learn from and draw musical insight from everything.”

“Stunned silence at the close of that session was broken. “I think we have just changed music.”

Rosenboom grew up on a small farm in west central Illinois. Agriculturally it was unproductive, but looking back he recognizes intellectual curiosity as the sustaining “soul food” of the family home. In a makeshift laboratory, set up in the attic, he assembled his own apparatus and made explorations in chemistry, electricity, physics, astronomy, and acoustics. At age five, he displayed lively interest in an upright piano, so his parents arranged for a trio of Catholic nuns (who ran a high-school conservatory in Quincy) to give him piano and violin lessons. Fine instructors, they also provided a sound grounding in music theory and conducting, and encouraged Rosenboom’s burgeoning interest in composition.

Well trained from the outset, he has remained insatiably inquisitive. Entering his teens, Rosenboom was given an old silver trumpet. “I taught myself to play by calculating valve combinations and tube lengths necessary to resonate with notes of the musical scale. Then I’d sit in the woods for hours blowing that horn. I never had a formal lesson, but I got to a point where I could play the Haydn concerto.” That remarkable self-discipline, analytical rigor, and aesthetic commitment have continued to sustain Rosenboom as a mature performer and composer.

When he enrolled as a student at the University of Illinois, during the mid-1960s, he already had considerable experience as a performer of classical orchestral and chamber repertoire and appeared to be set on that trajectory. Some teachers expressed disappointment when he opted to devote time and energy to investigative musical research rather than an interpretative role. Others, including Salvatore Martirano, Kenneth Gaburo, and Lejaren Hiller, supported his exploratory inclinations. The Urbana-Champaign campus introduced Rosenboom to computer engineer James Beauchamp’s sound synthesis techniques and biological computing models developed by cybernetics expert Heinz von Foerster. Fascinated by such innovation, Rosenboom began to envisage potential applications in the wider world. “Even in my early explorations,” he affirms, “my real interest was to bring new compositional ideas into live performance.”

Leaving Illinois in 1967, Rosenboom was appointed to work for a year in the stimulating context of SUNY’s Center of Creative and Performing Arts, in Buffalo. During this period he played drums with Think Dog!, ostensibly a rock group, actually dedicated to the pursuit of “genre-denying music.” He also played viola on a hugely influential recording of Terry Riley’s mesmeric tour de force In C. Stunned silence at the close of that session was broken, Rosenboom recalls, by producer David Behrman’s prophetic announcement, “I think we have just changed music.”

Relocated to New York City, Rosenboom got to know La Monte Young and joined his legendary drone ensemble The Theatre of Eternal Music, performing with the group at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, a festival in France, and the 1972 Munich Olympics. Electronic composer Morton Subotnick became an especially helpful friend and valued collaborator in New York. He made his Bleecker Street Studio available for Rosenboom’s use and introduced him to other innovative musicians. It was through Subotnick that Rosenboom became, for a while, artistic coordinator for Manhattan’s countercultural nightclub Electric Circus.

Another important figure was Ted Coons, a psychologist who had trained as a composer. Rosenboom describes him as a “professional catalyst, introducing to each other people who would generate extraordinary collaborative sparks.” Such input from Coons was a vital ingredient of multimedia performance events hosted by the Electric Circus. Rosenboom was an enthusiastic participant in those cross-disciplinary experiments. Crucially, it was through Coons that Rosenboom’s inquiring mind became aware of early research into biofeedback.

Before long that awareness precipitated “Portable Gold and Philosophers’ Stones,” his alchemical translation of brainwaves into musical forms. Appointment as professor in the Music Department of Toronto’s York University enabled Rosenboom to set up a laboratory for experimental aesthetics, affording him the opportunity to look into relationships between aesthetic experience and information-processing modalities of the nervous system. He published a written report, Biofeedback and the Arts: Results of Early Experiments, and conceived On Being Invisible (1976–77) that he describes as “a self-organizing dynamical system rather than a fixed musical composition.” The changing states of consciousness of a solo performer, wired to a computer that analyses brainwave signals, were channeled through electronic instruments designed by synthesizer pioneer Donald Buchla.

Music, for Rosenboom, is not a fixed set of rules, values, or techniques but an investigative arena where models may be floated as propositions, then brought into being through whatever resources are available.

Brainwave music and its concomitant notion of listening as performance constitute an important strand within Rosenboom’s multifaceted creative output. In 2014 computational neuroscientist Tim Mullen and cognitive scientist Alex Khalil became his collaborators in the realization of Ringing Minds. Tools developed for epilepsy research were adapted by Mullen for use by an ensemble of four brain-music performers. In live presentation Rosenboom improvised on electronic violin and Khalil played a xylophone made of stone. The wired-up listeners responded at a neural level to what they heard. “We treated this data as if it were arising from a collective brain,” Rosenboom explains. “I built a software-based electronic music instrument for this work that generates a vast sound field of ringing components.”

Readiness to draw upon the expertise and ingenuity of researchers across a range of disciplines has persistently characterized Rosenboom’s approach to music-making. With Donald Buchla he recorded an LP indicatively entitled Collaboration In Performance (1750 Arch Records, 1978).

Playing live has always been vitally important to Rosenboom; working with others no less so. “Collaboration requires shifts in the way we regard material we believe we originate, towards a deeper understanding of group consciousness,” he observes. The record with Buchla presents a section from Rosenboom’s How Much Better If Plymouth Rock Had Landed On The Pilgrims, an epic composition overall, musically polyglot. It also features an extract from And Out Come The Night Ears, with his propulsive Steinway piano interacting synergistically with a Buchla 300 Series Electric Music Box.

“I have certainly continued to draw on the instrumental technique I gained from my training,” Rosenboom acknowledges. “But I take a composerly approach to practicing the piano. I think of improvisation partly as composing yourself as a musician.” His fluency and exhilarating vigor at the keyboard have drawn Rosenboom into the company of comparably exceptional instrumentalists. A taste from the mid-’70s of his remarkable performances with Texan pianist J. B. Floyd and Indian percussionist Trichy Sankaran is preserved on Suitable For Framing (Mutable Music, 2004). While teaching at Mills College in Oakland, CA, during the ’80s, Rosenboom formed a stellar trio with saxophonist Anthony Braxton and percussionist William Winant, and in 1986 he joined Braxton’s superb improvising quartet, alongside drummer Gerry Hemingway and bassist Mark Dresser, for a European tour. The dynamism of his musical relationship with Braxton is volubly displayed on Two Lines (Lovely Music, 1994).

Other notable collaborations have included a wittily ironic songwriting partnership with performance and visual artist Jacqueline Humbert; projects with renowned theater director Travis Preston; and AH!, conceived with poet Martine Bellen as an opera generator, a template for countless operas receptive to input from composers around the world. Rosenboom’s Systems of Judgment (1987) may involve a sophisticated array of computers, synthesizers, samplers, and home-built circuitry, but it was written with Duncan MacFarland’s choreography in mind. More recently Rosenboom has worked with Indonesian choreographer Sardono Kusumo creating electronic music for Rain Coloring Forest (2010), while for Swarming Intelligence Carnival at the 2013 World Culture Forum in Bali he processed field recordings to produce immersive sonic environments.

“I was never able to develop an interest in crafting a musical style. I give myself the freedom to learn from and draw musical insight from everything.”

“It’s important to give oneself license to create new practice without the requirement that it be based on extant practice,” Rosenboom asserts, “to have free access to information, sources of inspiration, and facilities with which to make new work, no matter the media context in which these tools may traditionally be imbedded.” In 2015 he participated in a collaborative Los Angeles production of Hopscotch, a dramatically innovative “mobile opera for 24 cars” directed by Yuval Sharon. Battle Hymn for Insurgent Arts, presented in 2018, involves a feisty combination of Rosenboom’s music with images by animator Lewis Klahr, and texts drawn from writers ranging from Ovid to Lawrence Ferlinghetti.

At York University, Mills College, and CalArts, Rosenboom has had the good fortune to alight in institutions at which he could nurture “happy homes for the experimental.” Cultivation of favorable working environments has been an integral dimension of his creative life. An especially important friendship was formed when composer and theorist James Tenney took up a post at York. “We were both interested in algorithmic composition, which involves a huge range of possible model investigations,” Rosenboom recalls. “We talked about models for neural network systems, black holes, quantum gravity, harmonic perception, the nature of matter, evolution, and on and on. Most of what we call theory in music merely provides a language for retrospective analysis of styles and forms. It was clear that we didn’t have analytically useful languages for much new music, or for music outside European and American classical traditions. My approach was to start inside the brain, to investigate parsing principles evident in neural network signal processing and then to work outward towards musical experiences.”

“Stars do ring like big bells.”

That outward journey has assumed no limits. Rosenboom’s monograph Collapsing Distinctions (2004) poses the question: “What can we learn from experimental music that might aid us in interstellar communication?” His piano piece Bell Solaris (1998) invokes acoustic vibrations of the sun. “Stars do ring like big bells,” he affirms. “The sound with which music, as I see it, can deal, might include cycles of emergence and dissolution of universes, or very high-speed cycles found on the scale of quantum particles or waves.” The findings and speculations of science do not circumscribe his creative aspirations, however. Naked Curvature (2001), Rosenboom’s “whispered chamber opera,” was inspired by the structure of A Vision, the cosmos delineated in prose by Irish poet W. B. Yeats with assistance, he claimed, from occult instructors. Rosenboom’s music thrives on the elaboration of unexpected connections.

Music, for Rosenboom, is not a fixed set of rules, values, or techniques but an investigative arena where models may be floated as propositions, then brought into being through whatever resources are available. Whole domains of thought and modes of being can be summoned up through emergent sonic forms. “I love complexity,” Rosenboom acknowledges, “not because it represents some higher level, but because it is another name for a rich sound world which one might explore endlessly, discovering extraordinary relationships that can only be found through active imaginative listening. My piece with Salvatore Martirano, BC–AD I (The Moon Landing), which we presented at a concert in July 1969 to accompany live televised images of Apollo 11 descending to the Sea of Tranquility, explored the nature of nonlinear dynamics and thresholds of change embodied in circuitry built into an instrument. The most important thing was listening, and then understanding how electronics could open onto new worlds.”

Notes on the page, sounds in the air and ear are just part of the music-making process. Instrumental design, conceptual modelling, and initiating ideas are no less vital. Rosenboom understands music as a model-building discipline as much as a means of expression. It is a laboratory, a field of investigation and discovery, a continuously evolving world view. “No individual piece can expose the full territory of a particular propositional world,” he says. “If particular emergent forms don’t continue to provide rich territory for new discoveries, I move on. If they do, I think about ways in which I can share those territories with others.”

PART II

Educator and Dean

By Mark Swed

Over the past half century, including the last three decades as dean of CalArts’s Herb Alpert School of Music, David Rosenboom has set about radically transforming the training of composers and performers. He has done this as a music theorist; a scientist having studied the complex relationship between music and the brain; an instrument inventor and builder; a leader in electronic technology. That is a rare and excellent résumé for any dean.

The fact that he has done this (not only as, but because he is a pioneering composer and performer operating at the center of the American avant-garde) is what has made all the transformative difference in the world. For Rosenboom music education has been an ongoing composition—the realization of it, an ongoing performance.

The result is that from his CalArts aerie, Rosenboom has been a crucial, if under-the-radar, force behind a Los Angeles new music renaissance closely watched, massively envied, and unashamedly copied in cultural centers around the country, with Europe taking note as well. In June, though, Rosenboom steps down from his deanship, relinquishing administrative duties but continuing to teach, allowing himself to put more time and energy into his own music.

Meeting with Rosenboom in his campus office last August, as he began to prepare for his final school year (and about to turn 72), I asked why now? Only to have him, with a chuckle, point a finger. I—and a chorus of others! —had complained that after New York’s Whitney Museum of American Art opened its new Chelsea museum in 2015 with a retrospective, it had become all too evident that Rosenboom’s music is not out in the world as much as it should be.

Readying himself for radar detection is a long story. Rosenboom, who describes himself as coming “from a relatively poor family that lived on a small farm” in the Midwest, gives perhaps a bit too much credit to luck. The good fortune was an upright piano in the house of a child who took to it immediately. Lessons began at age five and, with musical aptitude evident, violin lessons a year later. The rest, however unlikely, seemed inevitable.

In the nearby town of Quincy, IL,his parents found a Catholic high-school conservatory run by three nuns who offered rigorous training in theory and performance. Before long Rosenboom was mastering the major piano literature and virtuoso violin concerto solos. Drawn to the avant-garde excitement of the 1960s, he began composing as well. That led to the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign (200 miles away) with exceptionally advanced music departments, including a pioneering computer music program.

There, as an undergraduate, he came under the spell of the flamboyantly controversial Salvatore Martirano, whose music included a Vietnam War protest piece for a performer in a gas mask. This was a place where a promising student could get noticed. Still an undergraduate racing through the curriculum, Rosenboom got a call from composer Lukas Foss, then music director of the Buffalo Symphony, inviting him to join the three-year-old Center for Creative and Performing Arts he had founded in the music department of the local State University of New York campus. They needed a violist. “Sal said, ‘you can’t pass that up,’” Rosenboom, who played violin not viola, recalls. “I drove to Chicago and bought a viola.”

In Renée Levine Packer’s history of the Center, This Life of Sounds, the former administrator describes the 20-year-old Rosenboom arriving in 1967 as a “composer-violist and award-winning young scientist.” Terry Riley was also new to the Center, which had become a hotbed of new music. Morton Feldman was on the faculty. John Cage and the New York School composers and performers found it a hospitable place to do projects.

Rosenboom immediately got busy at what would be his life’s work as a composer, performer, and educator, namely taking music apart and putting it back together with new systems of notation, new instruments, and new thinking about the brain, all in the effort to a return to the essence of music as the art of sounds. Buffalo was his laboratory as well as playground, where he not only found his voice as a composer but took part in a number of now legendary performances, such as the first recording of Riley’s In C, which precipitated music’s Minimalist movement.

Still, while Buffalo had its important Center, New York City was the center, the magnetic core of it all. After Buffalo the young musician joined the freelance life of a New York artist. He became associated with the Electric Circus, the city’s hippest disco, hospitable to both the Velvet Underground and Morton Subotnick, who later founded CalArts’s electronic music studio with his synthesizer. The downtown Manhattan new music scene gave Rosenboom exposure as a composer, and at the same time the resources to further research music as a biofeedback art, his increasing obsession. What it didn’t provide was much of a living.

The phone rang again. It was York University in Toronto inviting Rosenboom to start, along with three others, a music program from scratch. Not having even completed his bachelor’s degree at Urbana-Champaign, Rosenboom thought like a composer, like a performer, and like a scientist, not an academic. After a year in Toronto, he took a break to study experimental psychology at New York University where he learned research techniques needed to develop his ideas for York. Rosenboom was now ready to begin reinventing the curriculum.

“York taught me that, yes, one can develop confidence in the conservatory model, but it isn’t the best for highly creative, self-motivated people who want to develop something.

“I had felt held back in Illinois. While working on developing new notation systems and extended instrumental techniques, along with exploring electronics, I found that I could learn on my own much faster than the curriculum model permitted. It felt like there needed to be a more pliable approach for people trying to plow new territory.

“Studying with David Rosenboom was completely freeing and inspiring. He found music in every living (and nonliving) thing. I felt the limits of tonality disintegrating and a whole world of possibility opened up. David always championed my work. His belief in me helped me believe in myself.”—Ellen Reid

“In Buffalo I developed a notation language for raw sound that was just about how sounds start, stop, and evolve from beginning to end. I created configuration spaces.” One of these, which came to be key to his work at CalArts, was a piece structured as large circles of chosen pathways agreed upon in advance by a group of players who followed different parameters of music plotted out in figure-eight pathways.

“At York,” Rosenboom continues, “rather than begin with a particular language of music or a particular lineage of music, we took the materials of music and reduced them down to their abstract fundamentals.” That way ear training, for example, becomes about hearing raw sounds, first learning to discern their acoustic and perceptual differences.

“Can you measure it?” he asked his students. “Can you then make a scale out of those measurements? Can you then develop compositional materials out of that? Can you apply that to the form of the piece? And then can you apply that to spontaneous creation like an improvisation and to structured notation or instrument design or whatever it might be? That would be one pathway, one way of looking at it.

“Can you then develop the course material? That relates directly to what we’ve done at CalArts, because we’ve finished just the first year of a completely redesigned, or what I call a rearticulated, curriculum. It tries to make sense out of the plethora of potential pathways that a student could take and still come out with a broad set of tools that are very highly developed, yet allow the musician to function in a wide range of circumstances.”

Rosenboom has skipped ahead. He left York at the end of the ’70s, not wanting to commit himself to spending the rest of his life in Canada, and moved to Oakland, CA, where he then headed the Mills College Music Department in the ’80s.

At Mills’s progressive music department (where Darius Milhaud, Luciano Berio, and Robert Ashley had been on the faculty; where Morton Subotnick and Pauline Oliveros had been involved with creating a groundbreaking electronic music studio) Rosenboom was able to take his educational ideas, along with composing and performing, into a new realm.

“You say, here’s what’s going on at the cutting edge,” he explains of his approach at Mills. “You seem interested in that, so go right to it. Let’s work on a project right here. The students then participate like apprentices. They learn right away the skills they need to be contributors to this project, thus making projects a basis of learning. I liked to show students, here’s a chord in a Brahms rhapsody. Here’s a piece by John Coltrane and it’s got the same chord. What’s that about?”

Rosenboom cites his motivation to leave his cushy tenured position at Mills for what seemed at the time an uncertain. At CalArts the ambition of Steven Lavine, who had been installed as president two years earlier, was to refashion the School of Music. “I found a collection of very nice people of different but also overlapping ideals and interests,” Rosenboom says of his first impression upon arriving in Valencia. “But all were off in their own corners, in an atmosphere of what I would describe as kind of administrative neglect.

“I came in with the idea of building, like a composition, something. So, we started little by little by little. I had been in institutions long enough to know that it takes five years to get going, and then eventually you can get some momentum. Eventually we built up the school. It’s now, with over 300 students, nearly three times the size than it was then. Bigger may not always be better, but we didn’t have a critical mass to make things happen.”

One of Rosenboom’s first major moves was to create a performance program. “The separation of performers and composers was coming to a close, and I thought that would be key to moving forward. The writing was on the wall that the outside professional world was going to change. The era of the overly narrow specialist was going to be harder and harder for people professionally. Midsized orchestras were folding. The new model was to be able to do all kinds of stuff: play chamber music as well as in orchestras, do studio work, improvise, join rock bands, arrange, teach. And we slowly evolved towards that actually being the model, the multiplicity of skills.

“It took many, many years to make a curriculum that allows students enough ability to customize on how they draw on specialization. We’ve only just gotten there. Now you can be a performer-composer from your freshman year all the way to your doctorate.”

This has also meant the radical move of getting rid of specialties. Instead of having 300 students pursuing 30 different majors, be they violin, trumpet, musical technology, or whatnot, Rosenboom wanted the school to look like the people in it. Everyone is a composer-performer of a sort, and under this single umbrella there are clouds of expertise that can be drawn on to fit individual needs and interests, to teach the needed skills for Rosenboom’s project model of learning.

Virtually every student in the school makes original work of one kind or another, and what this has led to now is the army of young musicians participating in a music scene where the cutting edge is in such LA ensembles as wildUp and wasteLAnd. The musicians must not only be top-notch players able to function in any style or genre but also part of the creative energy of the group.

The next big step has been a morphing of everything into “musical arts” in which it’s all been turned upside down. In a program Rosenboom calls experimental pop, for instance, rather than a cookie-cutter singer/songwriter program, the fastest growing “specialty,” the students are drawn into literature studies and creative writing as well as given access to all areas of musical study.

Rosenboom’s vision is a world in which you can have a single specialty or more than one, or none. “You can declare no specialization and graduate with a BFA in music. What could you do with that?” he asks with another of his little chuckles. “You could go into musicology, however rigorous. Or you could go to law school or”—just as Rosenboom has—“do all kinds of things.”

On Saturday evening of CalArts Weekend, October 12, David Rosenboom, Dean of The Herb Alpert School of Music conducted and performed his Portrait Concert, Propositional Music, at the Wild Beast on the CalArts campus. The first of five pieces performed was Portable Gold and Philosophers’ Stones (Deviant Resonances, 2015). Here is an excerpt of that performance, awork for live electronic music and computer analysis of brain signalsby David Rosenboom, Sarah Belle Reid ’15 and Andreas Levisianos ’15.