“Okay, Okay, Okay, Okay. Challenge accepted.”

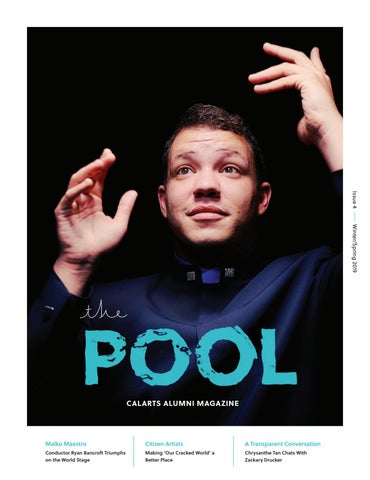

Composer Ellen Reid (Music MFA 11), recipient of the 2019 Pulitzer Prize in Music, is making me a playlist. She closes her eyes and sways while spinning records in her head, blurting out ideas and enthusiastic reasoning for her choices.

Ellen isn’t the kind of composer I learned about growing up. She doesn’t compose from a pedestal, entertain notions of artistic purity, or get lost in the “academia of it all.” Rather, she invites people in, encouraging them to engage with her art: participate, push boundaries, share stories, and heal.

I cannot overstate the impact of prism—Ellen Reid’s Pulitzer Prize-winning opera—and I say this as someone who regards major award winners with skepticism. On a general, topical level, prism is about sexual assault, a subject I normally avoid due to fears of being triggered. But prism feels entirely different. For me, it is an exhalation of pent-up frustration and self-blame. It’s a relief to encounter a work that focuses not on the forensics, legalities, and reparations of sexual assault, but on the survivor’s journey through post-traumatic stress. It’s messy! Living beyond trauma involves far less self-assurance and far more naiveté, self-denial, and inconsistency than most people think. The music of prism, assisted by librettist Roxie Perkins’s nonlinear storytelling, demonstrates this slippery narrative. We encounter a musical motif that recurs throughout the three acts in vastly different styles and with shockingly different sonic treatments—sometimes dreamy and romantically classical, embodying the alluring fantasy of denial, while at other times, gritty and processed through electronics, insisting that we look at the ugly things that have happened.

Ultimately, any survivor decides whether to accept the realities of their trauma. Notably, the motif also shows up during the pop-up nightclub that takes place in the theater during intermission. It is a seed that neither protagonist nor audience can forget.

Though Reid’s portfolio and accolades are already astonishing, she really lights up when talking about her Luna Composition Lab, the mentorship program for young, female-identifying, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming composers that she cofounded with composer Missy Mazzoli. It is Reid’s mission to empower and mentor the next generation of traditionally underrepresented composers, and she practices what she preaches.

As a composer, I look up to Ellen. As a human being, I feel companionship with her. Take everything you know about opera and classical music and destroy it, because this is Ellen Reid we’re talking to.

Chrysanthe Tan: Hi, Ellen! This won’t be an “interview” as much as a casual conversation.

[A plane flies low overhead.]

Ellen Reid: Wow!!! Look at that! Did you see that? The plane was pulling the clouds like it was smoking or something!

[We stare at the sky.]

Well this is an oddly fitting way to start our conversation. Your attention to sensory detail is something I notice and really appreciate in your work.

Thank you! I always think of points of entry. It’s important to create multiple points of entry within a work for people to get something from it. With a narrative or dramatic work like an opera, you have the visuals, but I love making sound installations too, because they’re like tactile windows in for people. I just built an interactive sound sculpture titled Playground with an opera company in Omaha, NE, and all the elements of the swing set made noise.

“We focus so much on the incident and not nearly enough on the aftermath and trauma for the survivor.”

The swing set also happened to be made of things that cause carbon pollution. In the end, we had this heavenly looking, silver sculpture that sounds beautiful and that you watch children play on—but then, when you look closely, you see that it’s made of exhaust pipes, mufflers, oil barrels, and plastic straws.

There are so many levels to that. You can think about the pollution, play on it like a normal swing set, or even enjoy the beautiful sound of it.

You can also think about the meta of what this all means about childhood. … Or just hit things. It’s a playground. I mean, who doesn’t want to hit percussion?

I can’t get over the fact that you squeezed a nightclub into the intermission of your Pulitzer-winning opera. That’s a pretty big example of an alternate point of entry. prism really surprised audiences of all backgrounds in the best way possible. I feel that you also broke protocol in terms of how we, as a society, have tacitly decided to dance around the subject of sexual assault.

We focus so much on the incident and not nearly enough on the aftermath and trauma for the survivor.

I agree. Your opera is therapeutic for me. What’s the best audience response you’ve gotten to prism so far?

I received an e-mail from someone who said they had never felt those emotions before in their life. It took me a while to process that. And I’ll never forget the audience response in São Paulo. Right now, in Brazil, there’s a lot of pressure to defund art, major issues with women’s safety and women’s rights. So, the fact that this was a modern work by two women about sexual assault made these people feel really brave. They shared their stories and because of our piece, they convened a forum about women and art in Brazil. The amount of support and investment as well as the activism it inspired, just blew me away.

And now you have a Pulitzer. What’s that like?

You know, I haven’t had a Pulitzer for very long, but the thing external success brings is more possibilities and control over my career, which is great. I feel more agency. All of a sudden people listen to me.

A bit like winning a golden ticket to Willy Wonka’s chocolate factory?

Exactly.

External markers of success are so weird. You’ve been here all along.

I actually didn’t start writing until I was 19 and in college at Columbia University. Afterward, I lived in Thailand for two-and-a-half years. When I came back to New York, I was figuring out how to make sense of my interests and experiences—theater, Thai classical music, growing up in the American South and singing in church. I started looking at master’s programs, and CalArts was one of only two places to which I applied. I loved the freedom to explore different programs within the music school and connect with other schools as well. I felt lucky to have such opportunities. And now, with all this external success, one of the first things I think about is the Luna Lab.

Oh my god, I’m such a fan of the Luna Lab. That’s the fellowship program you cofounded with Missy Mazzoli for young, female-identifying, nonbinary, and gender nonconforming composers, right? I wish it had been around when I was starting out. What a dream for the fellows!

As soon as I won the Pulitzer, I was like, “Holy shit, these Luna Lab Fellows are going to be able to go way beyond this now.” It made me feel like my career was about more than my own career. I want to forge a path so it’s easier for the next generation, and now I’m even more empowered to do that.

I love your perspective. Is there a dark side to your success?

It is very chaotic. For a while I lost track of where normal was, you know? The most challenging thing—which is also one of the best things—is that a lot of people suddenly wanted to communicate with me after winning the Pulitzer. It’s so great to be in touch with all these people, but there’s also so much energy and time needed to communicate. I have to be intentional in carving out writing time. But how does anyone carve out time to practice their craft as they keep advancing in their career? It’s a challenge.

Good question. How, exactly, are you managing to do it?

I stick to banker’s hours, or rather, academic’s hours, as much as possible. Instead of 9 to 5, it’s 10 or 11 to 7 or 8. I schedule meetings in the afternoons, if possible.

Do you have rituals?

I like to burn things.

…?

I burn Palo Santo or incense. I always meditate and burn something before writing.

God, this all sounds so very … balanced. Were you always this disciplined?

Kind of, yeah. My parents were always pretty health conscious. In college I took up running to deal with stress. I still try to take a short jog every day, like a 20-minute jog after I’m done writing just to kind of come down.

Running is such a stress reliever! Good idea to do it after writing. I tend to do it before.

I honestly don’t push myself very hard, but if I’m traveling it’s a way to see the area. …

Okay, you’re speaking my language. Running is such a precious travel thing for me. You can cover so much ground, and I like to christen each city with a casual run.

Yes! Wow. Wait, do you get sentimental about your running shoes too?

Extremely sentimental. It’s bad for my feet, because I really need to update my shoes. But I’m like, “These shoes went to Vienna. …”

Yes! I’ve been to all these places in the world with my running shoes, and they probably have the dirt from India and São Paulo and the dirt from all these places on them. And you know, they’ve carried me through a lot of different places that I don’t even remember right now.

That’s so special. Can I give you a challenge before we say goodbye?

Okay.

“Winning the Pulitzer made me feel like my career was about more than my own career. I want to forge a path so it’s easier for the next generation.”

I know how important accessibility and points of entry are for you. So what are your top three listening recommendations for people who consider themselves unfamiliar with classical music?

Ooh. Daphnis et Chloé by Maurice Ravel, because it’s just the most beautiful thing ever. The music of Silvestre Revueltas is amazing. And West Side Story by Leonard Bernstein.

Wonderful suggestions. What would you recommend for people who already listen to classical music but aren’t familiar with 21st century, living composers? Most people I know are in this category.

Well, the cool thing about right now is that there are a lot of people doing things in between genres, like Qasim Naqvi (Music MFA 08) from The Dawn of Midi band. They use analog instruments to make synth sounds, and it’s quite compelling. Missy Mazzoli is a huge one, for sure. She’s not only a great collaborator, but her music speaks to more than a classical music audience. And Sarah Kirkland Snider. Her Unremembered album is one of my favorite things. So good.

Last but not least I want a playlist of your own music! I find it so special to hear recommendations from artists themselves. Can you recommend: (1) something to wake me up in the morning, (2) something to help me feel more at peace with myself, and (3) something to expand my mind and challenge me?

Okay, I’ve got stuff for you. For morning, I nominate several works: First, “Lost in the Blue” from prism. Second, “Fear-Release,” which I wrote for Los Angeles Percussion Quartet (CalArtians, by the way), and is better if you just feel like staying in bed. And third, another track from prism titled “Run.” That one’s great if you need to get motivated and get your ass out of bed.

If you want to feel more at peace with yourself, you should really go to Playground and experience that sound installation. Otherwise, Petrichor is another good one; there’s a clip of that on the Los Angeles Chamber Orchestra’s Soundcloud.

And finally, a piece to expand your mind? … Okay. So I wrote a theme song for my friends Rhys Ernst (Film/Video MFA 11) and Zackary Drucker (Art MFA 11) —another collaboration with CalArtians, by the way. Their Whitney Biennial installation was a talk show with a trans woman as host, so I wrote a theme song that’s like a cheesy-ass saxophone with a lot of reverb. My friend ran the saxophone through GarageBand and put a lot of reverb on it just to make sure it still sounded cheesy enough. Then Zackary asked me to put, like, five minutes of massive applause at the end of it. It’s pure camp, and it makes perfect sense in context. It’s called “You’ll Love It! Theme Song.”